Hyuncheol Bryant Kim is an Assistant Professor in the department of Policy Analysis and Management at Cornell University, as well as in the Department of Economics, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology; c0-authors include Booyuel Kim (Graduate School of Environmental Studies, Seoul National University), Cristian Pop-Eleches (School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University), and Jaehyun Jung (Korea Institute of Public Finance, Sejong).

Sub-Saharan Africa has been the region most impacted by HIV/AIDS with the area accounting for two-thirds of the 38 million people living with HIV worldwide in 2019 (1). While progress has been promising with effective treatments that reduce viral loads and new global HIV infections down 40 percent from peak levels in 1998, much work remains in the eradication of the disease (1).

Medical male circumcision has been promoted as one of the most cost-effective HIV prevention strategies especially in Sub-Saharan African countries with high HIV incidence. Randomized control trials (RCTs) have shown the efficacy of male circumcision in reducing female-to-male HIV transmission risk by 51 to 60 percent (3) (4) (5). Additionally, male circumcision reduces herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection (6).

However, there is a concern that male circumcision programs might have limited impacts in the reduction of infections due to risk compensation. In other words, could reduced risk from male circumcision lead to an increase in risky sex behaviors? Studies have shown limited evidence of risk compensation following male circumcision but are generally based on self-reported data in short term follow-ups. The aim of the study is to assess the long-term impacts of medical male circumcision on risky sexual behaviors as well as HIV-1 and HSV-2 infection.

We implemented a clustered randomized controlled trial of a male circumcision intervention with four years of follow-up. Almost 2,200 male students enrolled in 33 secondary schools near Lilongwe, Malawi. Between October 2011 and May 2012, eligible male participants were assigned to the intensive intervention group (n=1,342) and to the less intensive and delayed control group (n=851). For both transportation support interventions, students could choose either a direct pick-up service or a transportation voucher that could be redeemed at the assigned clinic performing free circumcisions. For the intensive intervention, the direct pick-up service was offered six-times and the transportation voucher was offered twice over a period of 18 months. For the less intensive intervention, the direct pick-up service and the transportation vouchers were offered once over a period of 6 months. The primary outcomes are HIV-1 and HSV-2 infections four years after the offer and a series of self-reported measures of sexual behavior four years after the offer. Analysis was intention to treat.

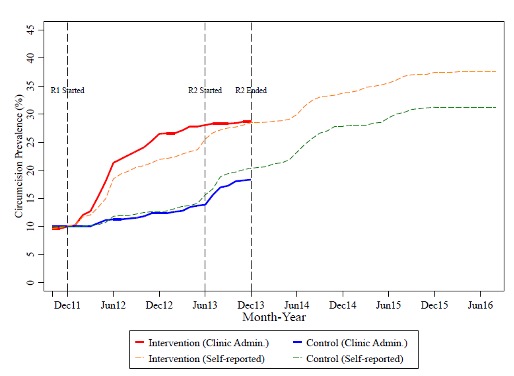

Figure 1 shows the cumulative prevalence of male circumcision over time based on hospital records and self-reported data in the follow-up. Baseline circumcision rates were 11.0% and 10.6% in the treatment and control group, and the difference is not statistically different. We prefer to rely on hospital records data since self-reported data may suffer from recall bias.

Due to the difference in intensity of transportation support, 221 (18.6%) out of 1,162 students in the intervention group and 61 (8.2%) out of 736 students in the control group were additionally circumcised at the assigned hospital during the first two years following the intervention. The difference was reduced but still remained after four years.

After four years in the intention-to-treat population, the cumulative probability of HSV-2 infection measured by IgG (showing life time infection) was 11.7% in the treatment and 8.4% in the control group. For recent HSV-2 infections measured by IgM (showing recent infection), infection rates are 2.5% in the treatment and 1.2% in the control group. In addition, we do not find significant differences in the prevalence of HIV-1.

At baseline, we find no difference in self-reported sexual behaviors. At the 4-year follow-up, we find a significant increase in sexual behavior among males in the intervention group compared to the control group. Risky sexual behavior was measured from survey responses using the Item Count Technique (ICT) and condom purchase. Using the ICT we analyze responses to two sensitive questions about risky sexual behavior: (1) “I think I have to use a condom in case of sex with somebody that I do not know well” and (2) “I had sex with more than two people in last 12 months”.

The ICT suggests that 38% of students in the treatment group and 61% of students in the control group think that they have to use a condom in case of a casual sexual encounter. For the second question, the differences are 6% in the treatment group and 15% in the control group and are not statically different from each other. There is also no statistically significant difference between the groups in the likelihood of purchasing a condom.

We also measure self-reported sexual behaviors. Risky sexual behaviors, measured by using an index of eight major risky sexual behavior indicators, increases among males in the intervention group compared to the control group even though it is not statistically significant. We also study each component of risky sexual behaviors. It is worth noting that all our results that are statistically significant are related to condom use: The increase of reporting an inconsistent use of condom and unprotected sex with last partner are mirrored in the ICT results on the changes in attitude regarding condom use for casual sex.

In sum, we find evidence of risk compensation that diminishes preventive effect of male circumcision on HIV-1 and HSV-2 infection. Specifically, we find a long term increase of HSV-2 infection among the male circumcision treatment group while there is no significant change in HIV-1 infection. Risky sexual behavior measured using the ICT technique provide complementary evidence to the results using the bio-markers. We also summarize the results from a simple simulation, which tries to understand whether our large effects can be explained through reasonable levels of risk compensation taken from the available literature. The simulation exercise results suggest that the relatively large treatment effects that we estimate could be explained by changes driven by a combination of a selection effect as well as large but reasonable changes in risk compensation (i.e. probability of sex without condom increases by 30% and the frequency of sexual intercourse increases by 100%).

Using a community-based trial in male circumcision scale-up project for male secondary school students with the longest follow-up to date and a comprehensive set of outcomes, we provide evidence that male circumcision led to increased HIV-1 and HSV-2 risk behavior. Our results suggest that as male circumcision programs continue to be scaled-up, the monitoring of risk compensation remains important, as are efforts to supplement these programs with educational and public health campaigns aimed at reducing risky sexual behavior.

References

- UN AIDS. “Global HIV & AIDS statistics — 2020 fact sheet.” https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet

- New York Times. “Coronavirus World Map:Tracking the Global Outbreak.” March 20, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/world/coronavirus-maps.html

- Auvert, Bertran, Dirk Taljaard, Emmanuel Lagarde, Jolle Sobngwi-Tambekou, Rmi Sitta, and Adrian Puren, “Randomized, Controlled Intervention Trial of Male Circumcision for Reduction of HIV Infection Risk: The ANRS 1265 Trial,” PLoS Medicine, October 2005, 2 (11), e298.

- Bailey, Robert C, Stephen Moses, Corette B Parker, Kawango Agot, Ian Maclean, John N Krieger, Carolyn FM Williams, Richard T Campbell, and Jeckoniah O Ndinya-Achola, “Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial,” The Lancet, February 2007, 369 (9562), 643–656.

- Gray, Ronald H, Godfrey Kigozi, David Serwadda, Frederick Makumbi, Stephen Watya, Fred Nalu- goda, Noah Kiwanuka, Lawrence H Moulton, Mohammad A Chaudhary, Michael Z Chen, Nelson K Sewankambo, Fred Wabwire-Mangen, Melanie C Bacon, Carolyn FM Williams, Pius Opendi, Steven J Reynolds, Oliver Laeyendecker, Thomas C Quinn, and Maria J Wawer, “Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial,” The Lancet, February 2007, 369 (9562), 657–666.

- Tobian, Aaron A.R., David Serwadda, Thomas C. Quinn, Godfrey Kigozi, Patti E. Gravitt, Oliver Laeyendecker, Blake Charvat, Victor Ssempijja, Melissa Riedesel, Amy E. Oliver, Rebecca G. Nowak, Lawrence H. Moulton, Michael Z. Chen, Steven J. Reynolds, Maria J. Wawer, and Ronald H. Gray, “Male Circumcision for the Prevention of HSV-2 and HPV Infections and Syphilis,” New England Journal of Medicine, March 2009, 360 (13), 1298–1309.