Despite the agriculture sector being one of the most important contributors to economic well-being in Sub-Saharan Africa (World Bank 2008, OECF-FAO 2016) and its persistently low agricultural productivity, smallholders in this region are unenthusiastic about modern technology, such as fertilizer, and keen on traditional technology, such as intercropping.

This is a technology adoption puzzle: Why do African farmers not adopt modern technologies that economists believe should provide, on average, higher returns? At the same time, why do African farmers adopt traditional technologies that have been shown to be unprofitable?

In my job market paper, I examine the rationale behind farmers’ decisions about agricultural technology adoption and offer an explanation for this adoption puzzle. I build a structural model and estimate it using data from Tanzania. I suggest two potential mechanisms that influence farmers’ adoption choices. First, farmers are heterogeneous: farmers’ ability can differ, and plots’ quality can vary both within and across farmers. Therefore, the rewards from adopting the same technology can differ across farmers and plots. For some farmers, the additional benefit of adopting fertilizer is approximately zero. A higher return on average hence does not convince every farmer that a modern technology is superior. Second, farmers also care about risk, or the variance of returns due to the intrinsic characteristics of technologies. I find that when making technology adoption decisions, farmers consider both the individual mean and the variance of returns, thus good on average is not good enough.

A Vexing Puzzle

Many studies have investigated why African farmers do not adopt new higher-average-return technologies (Caldwell et al. 2019). Most of them focus on the obstacles that have caused inadequate adoption of modern technologies, such as information failures (Foster and Rosenzweig 1995, Munshi 2004, Conley and Udry 2010), supply shortages (Moser and Barrett 2006), and credit constraints (Duflo et al. 2008). While those factors contribute to the low and stagnant rate of technology adoption, they cannot fully account for it. After decades of technology promotion and rapid economic development, farmers now have access to technological knowledge and inputs. Yet, uptake of modern technologies remains low. This paper examines a different hypothesis: farmers’ decisions about adoption or non-adoption of technologies may be rational responses to the return distributions they face. I show that expected returns and variances of adoptions differ across farmers and technologies. More importantly, these differences could explain the variability in farmers’ technology adoptions.

I choose two agricultural technologies, inorganic fertilizer and intercropping. The longstanding promotion of inorganic fertilizer in Sub-Saharan African countries suggests that information and learning effects as well as the input availability constraints are unlikely to explain its persistently low adoption rate.

The adoption puzzle is explained by farmers’ dual considerations of heterogeneous profits and heterogeneous risks

I construct a farmer decision-making model and estimate it using the Tanzania Living Standard Measurement Study panel dataset. I first estimate the farmers’ production function using the correlated random coefficient model (Chamberlain 1984, Suri 2011), then estimate the intrinsic characteristics of technologies through the feasible generalized least squares method (Just and Pope 1979), and lastly analyze factors that influence farmers’ agricultural technology adoption decisions with the alternative-specific conditional logit model.

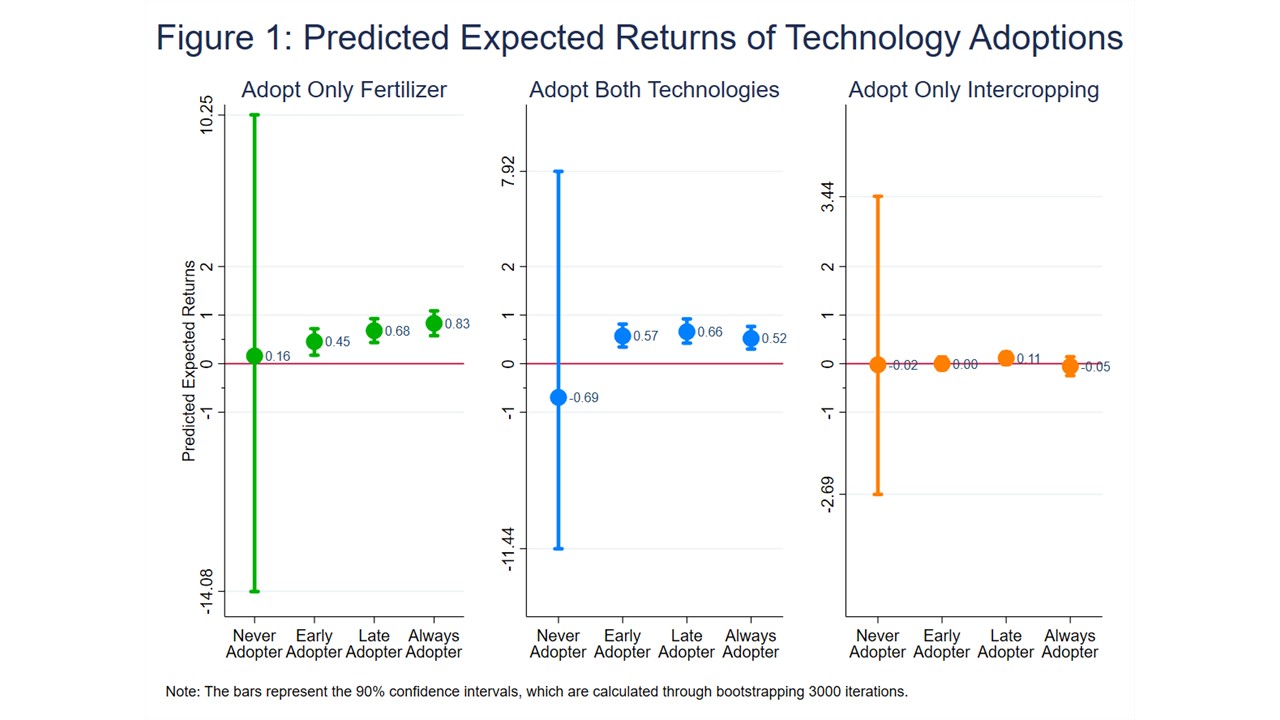

Based on farmers’ adoption history, I categorize farmers into four groups: never-adopters, who have not adopted the technology in any year; early-adopters and late-adopters, who are switchers and have adopted the technology in one year but not the other year; and always-adopters, who have adopted the technology in both years.[1]

Comparing the dots in Figure 1, which represent predicted expected returns of adopting only fertilizer (left), fertilizer and intercropping (center), and only intercropping (right), I find suggestive evidence that the expected returns of adopting the same technology are different across distinct types of farmers.[2] Looking at the first two panels, the (additional) expected returns are approximately zero for never-adopters if they have adopted the technology, while the (additional) expected returns for always-adopters are significantly above zero when they adopt the technology. The positive coefficients stand for an increase in yield of 126% for adopting only fertilizer and 66% for adopting both technologies. This evidence of heterogeneous returns indicates that farmers’ self-selections of technology choices seem to be correct given their farming abilities and plots’ qualities. Moreover, those sizable expansions in yield could be understood as a reason for adoption.

On the other hand, looking at the third panel, the expected returns of adopting only intercropping, are all close to zero. If the rationale for adoption is only based on expected returns, no farmers would ever adopt intercropping. However, during each farming season, about 50% of plots are intercropped. Accounting for intercropping’s impact on the variability of yield, suggests that farmers rationally adopt this technology. Figure 2 shows that adopting only intercropping significantly reduces the variance of yield, while adopting only fertilizer increases the variance of yield. Those two effects are different from each other at 5% significant level. This provides justification for the adoption of intercropping to reduce risk and the non-adoption of fertilizer to avoid risk.

On the other hand, looking at the third panel, the expected returns of adopting only intercropping, are all close to zero. If the rationale for adoption is only based on expected returns, no farmers would ever adopt intercropping. However, during each farming season, about 50% of plots are intercropped. Accounting for intercropping’s impact on the variability of yield, suggests that farmers rationally adopt this technology. Figure 2 shows that adopting only intercropping significantly reduces the variance of yield, while adopting only fertilizer increases the variance of yield. Those two effects are different from each other at 5% significant level. This provides justification for the adoption of intercropping to reduce risk and the non-adoption of fertilizer to avoid risk.

When deciding which technologies to adopt, the expected return has a significant positive influence and the variance of return has a significant negative influence on farmers.

The low adoption rates of fertilizer, a highly-promoted technology in Sub-Saharan Africa, are explained by two factors: some farmers have low expected returns to adoption based on their characteristics, making it unprofitable for them to adopt. Other farmers choose to avoid the high risk associated with fertilizer. On the other hand, many farmers adopt a seemingly unprofitable technology, intercropping, because of its ability to reduce risk.

Policy Implications

Two policy prescriptions arise from this study’s findings.

- Insuring production risk: Based on the counterfactual estimation, some farmers could earn higher returns by adopting fertilizer, but do not adopt it to avoid risk. Providing production risk insurance may nudge those capable farmers from their rational low-mean and low-variance equilibrium to a higher equilibrium, thereby improving farmers’ welfare.

- Developing low-variance technologies: Given the importance of variance on farmers’ decision making, policy makers and scientists should redouble their efforts to develop agricultural technologies that decrease the instability of yields. New technologies that feature risk-reducing attributes may hold the secrets to a green revolution in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Footnotes

[1] Since this research aims to examine the rationale of adoption and non-adoption, not farmers’ technology switching behaviors, I focus on the expected returns for never-adopters and the always-adopters. Estimations of the other two groups are presented as secondary results.

[2] This result is not conclusive, as the confidence intervals of the expected return for never-adopters are large. The expected returns for never-adopters are imprecisely estimated, mathematically because the estimates for the technology-specific aggregate return to revenue, βD, are inexact. The intuitive reasoning is still under investigation.