Implementing development programs in conflict-affected areas is crucial for conflict as well as poverty reduction. The big question is how do you carry out these programs successfully? Are there specific conditions under which development policies are effective? What is their impact on violence?

So far, evidence on whether development policies can reduce violence is mixed. Iraq is an example of where they have been successful, but in the Philippines violence has increased, possibly due to insurgents sabotaging government programs. Therefore, a sufficient level of security could be a precondition for development programs to work in conflict areas. Indeed, evidence from Iraq and Afghanistan support this idea. To test the hypothesis further, we looked at the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) and examined the factors that have been related to reduced violence in the area.

The conflict in Jammu and Kashmir

The low intensity conflict is rooted in the dispute between India and Pakistan over the territory of Kashmir, which began with the partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947. The dispute has led to two open wars, in 1947 and 1965, and brought the two countries close to war on several occasions.

The current armed insurgency started in 1989 in the Kashmir Valley, spreading over time to other parts of the state. The insurgency has been kept alive by support from Pakistan in the form of arms and training, while the Indian army runs a counter-insurgency operation together with the police forces. Between 1998 and 2014, it is estimated that the insurgency resulted in over 25,000 deaths. Violence has however been decreasing since the early 2000’s.

How did violence decrease?

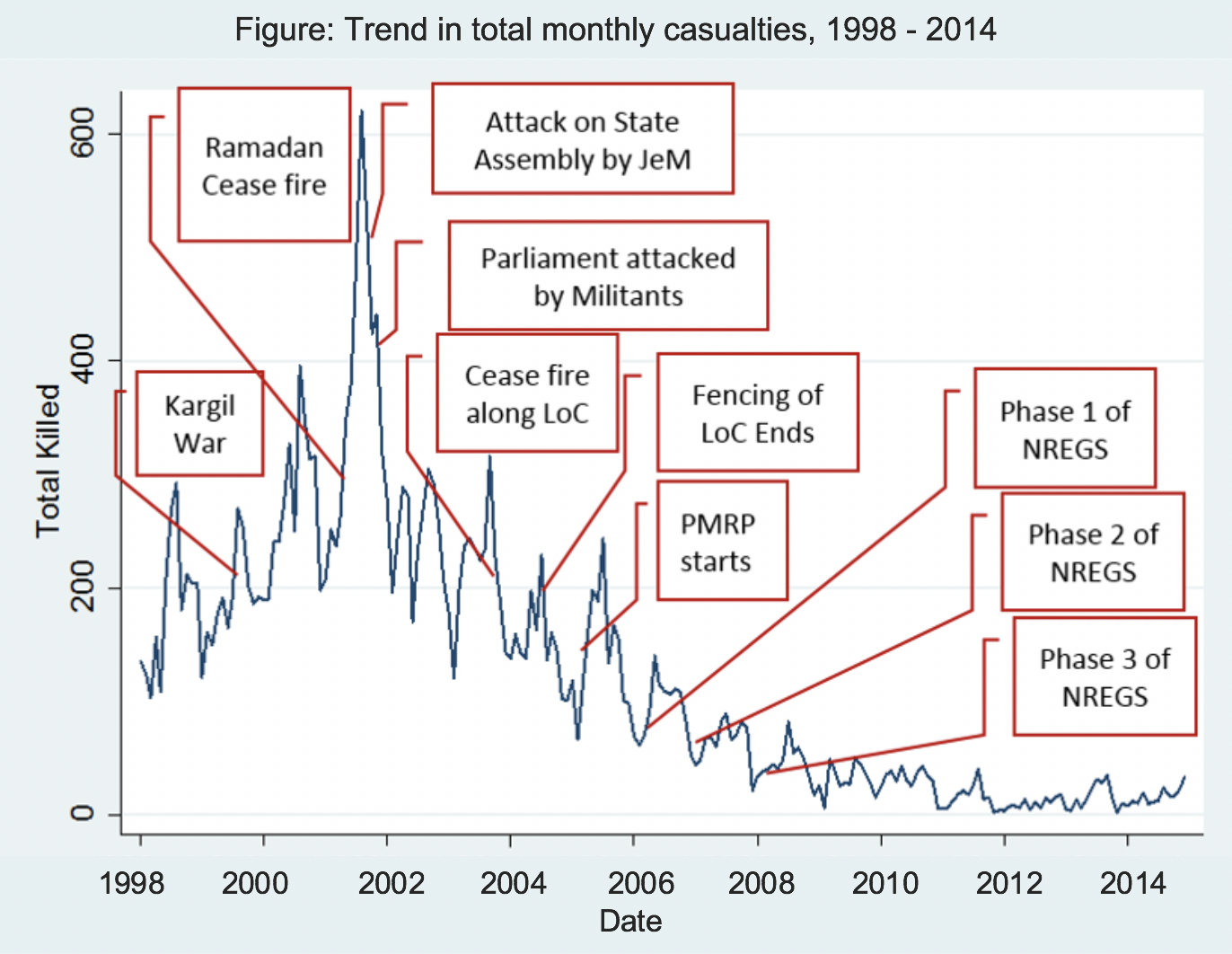

So why has violence in J&K decreased? We used information collected from newspaper reports by the South Asian Terrorism Portal (SATP) on insurgent, civilian and security personnel casualties and the number of incidents involving explosives as indicators of violence. Visualizing the data of total casualties in a graph (see figure), it does appear like there was a gradual shift from a ‘high violence regime’ to a ‘low violence regime’, a pattern that is visible for all the violence indicators.

We wanted to confirm whether this was the case and used non-linear time-series techniques to precisely detect structural breaks in the violence data. Using these techniques, we found that there has indeed been two ‘regimes’ of violence: a high violence regime between 1998 and 2003 and a low violence regime between 2007 and 2014. The period in between, from 2003 to 2006, can be seen as a transition period between the regimes, during which a “smoothed” structural break took place. The methods we used allow ‘the data speak for itself’ to inform us when critical changes in violence took place instead of testing whether certain events are associated with breaks in the time series.

Knowing when structural breaks have occurred is important as they often occur as a consequence of changes in policy. Having identified 2003-2007 as the crucial period during which there was a shift in regimes, we then asked the question: what policies were implemented during this period?

The JaisheMohammed (JeM) – A group that has carried out terrorist attacks in the region.

What happened in Kashmir between 2003 and 2006?

During this period several security and development related events took place:

- In 2003, at the beginning of the transition period, India and Pakistan agreed to a cease-fire along their border and restored diplomatic dialogue (suspended since the 1999 Kargil war).

- The construction of a 550-kilometer-long border fence between J&K and Pakistan was completed in September 2004. Indian security forces estimate that it has been successful in reducing the infiltration of insurgents from Pakistan.

- The Prime Minister’s Reconstruction Plan for J&K (PMRP) began in March 2005. Implemented by the then Prime Minister of India, Dr Manmohan Singh, its objective was the long-term development of the state building infrastructure, providing basic services and creating jobs. As of March 2014, over 13 billion USD (780 billion Rupees) had been disbursed.

- The roll-out of the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS) to J&K started in 2006, at the later stage of the transition period. Being one of the largest safety net programs in the world, NREGS guarantees 100 days of manual work at the minimum wage to all rural Indian households.

Were these policies effective in reducing violence?

Having identified structural breaks and the events which coincide with the breaks, we test if these events were effective in reducing violence using district-level violence data.

We found that security improved at the border after the completion of the fence. While there were more insurgent casualties in border districts, civilian casualties in the area decreased after the completion of the fence. This suggests that security forces were perhaps better able to target insurgents, thereby reducing civilian deaths. The NREGS and PMPR programs were also effective in reducing insurgent and security force casualties.

These results give support to our idea that there needs to be a certain level of security before development programs can work effectively. In the case of J&K, the construction of the fence improved the security environment, which allowed large-scale development programs to be implemented. The programs then further reduced violence, particularly that directed towards civilians.

Suggested further reading: Kaila, H., Singhal, S. & Tuteja, D. (2018). Do fences make good neighbours?: Evidence from an insurgency in India. Households in Conflict Network Working Paper 287.

This blog post was originally published at WIDER Angle, January 2019.