A persistent—and insidious—problem

Food insecurity remains a pressing issue for the development economics community; while it was the topic of only one dedicated session at NEUDC this year, it was pervasive as a cross-cutting topic across nearly all themes.

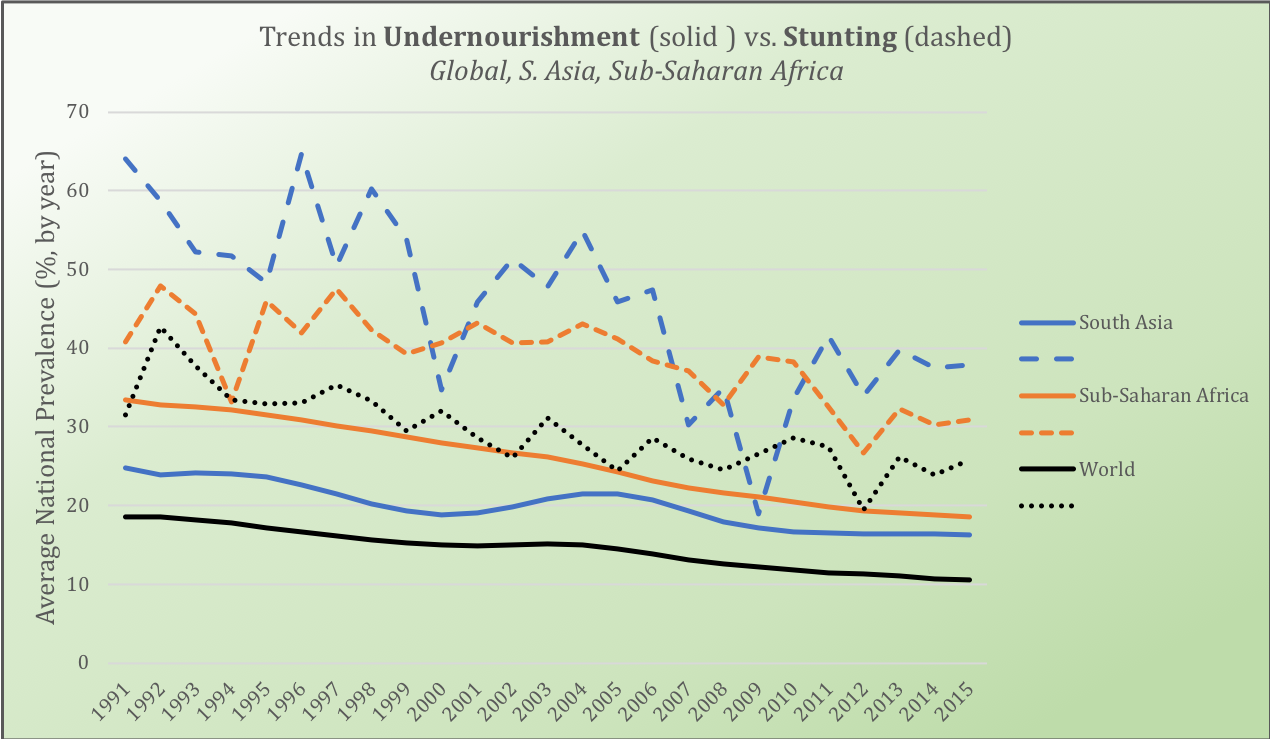

While one can point to extraordinary progress in combatting undernourishment in recent decades, this big-picture progress can mask the extent, and difficulty, of the problems that remain.

The national prevalence of the food insecure is lower and falling, but the raw numbers are still unacceptably high, and rising. Some food insecure people are neglected because they live in relatively better-off countries (such as in South Asia); others because they live in hard-to reach conflict zones. Moreover, the nature of the problem is now more complex; it is generally less about insufficient calories than about nutrients, which are harder to acquire. Even more challenging is the question of intra-household distribution; a household may be food secure while some of its members are not.

A growing body of knowledge…that doesn’t inspire much hope

Research presented at NEUDC highlighted a number of underlying factors that we know a lot (and are learning more) about, but can do little to affect through policy.

For example, an impressive cross-country study presented by Samira Choudhury confirms that parents’—particularly mothers’—education level (which is slow to change) is a known driver of child-level nutrient consumption. A deeper challenge lies in intra-household dynamics. As Rossella Calvi explained using evidence from Bangladesh, women’s weaker bargaining power can mean that women and children in a household can be food insecure, even when the household over-all is not (as also mentioned in Anaka Aiyar’s post on the gender theme, earlier in this series). The challenge arises because women’s bargaining power is hard to affect with policy instruments, especially in the short term.

Other features of the culture, context, and environment also drive food insecurity. Erwin Knippenberg and John Hoddinott find that land consolidation in Ethiopia is causally associated with greater food insecurity, due to the loss of the crop diversity and rainfall response associated with land fragmentation. And of course, climate change and weather-related shocks are a prevalent and increasing risk. Francisco Otieza explained one way agricultural output is likely to be impacted negatively by increasing temperatures (in Peru), especially for poorer, subsistence farmers. Farzana Hossain showed how even changes that could be positive – like increased rainfall – may have negative spillovers that exacerbate inequality and food insecurity. Finally, it goes without saying that conflict is an ongoing threat; conflict settings remain among the hardest to study (though some succeed in doing so, as discussed below).

So – what are the policy levers?

It’s not all gloom and doom; much of the research highlighted promising avenues for progress, across many domains of development research and policy.

For example, we are understanding more and more about the options for government-run and/or large-scale social protection programs, and the benefits and risks of different modalities. School feeding programs can have diverse, and awesome, benefits; India’s Mid-Day Meal Scheme (MDM) led, as Santosh Kumar explained, to improvements in anemia and cognition among participating children via the introduction of double-fortified salt. Harold Alderman and his co-authors show that the benefits of that same program for young girls are intergenerational, contributing to reductions in stunting among those children’s eventual children (as highlighted in Tarana Chauhan’s post 0n S. Asia). School feeding programs can often also succeed in insecure settings—such as in Mali, where Elisabetta Aurino showed from an experiment that school feeding had an impact on kids’ presence in schools as well as their ability to perform.

The debates around cash versus food transfers, and if and how to subsidize food, continue in the research community. Ben Schwab and co-authors find that there are relative benefits to cash transfers (over food) for investment in productive activities in Yemen. This finding was also supported by work presented by Andrew Zeitlin on cash transfers in Rwanda (see more on that in Sylvia Blom’s post). National food subsidies sometimes get a bad rap—but, Aditya Shrinivas argued that they can and do work, for example in the case of improved nutritional outcomes in India.

Thinking outside of the transfers box—there is significant potential for nutritional improvement, particularly in micronutrients, through agriculture and technology. Dan Gilligan showed promising findings in the area of bio-fortification, namely the willingness of Ugandans to adopt the vitamin-A-rich orange sweet potato and high-iron fortified beans. The straightforward iodization of salt improved women’s cognition and educational attainment in China, as explained by Zichen Deng. And, Leah Bevis’s current research points toward how enhancing zinc in soils can improve dietary availability of that essential nutrient.

Finally, learning is important. True, we cannot increase a mother’s level of education overnight; but information provision has great potential at relatively low cost. Seollee Park demonstrated that nutritional training for parents yields added benefits for children (relative to food vouchers alone), and Hope Michelson found that fertilizer can increase yields, but only when more nuanced information is provided to potential adopters.

Now what?

These promising findings should encourage the research community to further explore these frontiers. And, what is equally important, they should inspire us to continue to develop and test (and advocate for) actionable policy levers in order to combat the daunting food security challenges that persist in our global landscape.

At last! An approach to food security issues that does not suffer from an overabundance of rosiness! It has long been clear that economists need to get outside narrow professional niches if they are to contribute to a valid consensus on addressing nutritional security, and you cite some papers that move in this direction. Nevertheless, as a discipline, economics still has a long way to go. We individually produce bricks but collectively we have yet to build a structure. Only one session at NEUDC? Shame!

Thank you for your comment! My research on different aspects of food security has convinced me that, while there have been many steps forward, the problems that remain are the most intransigent; so I too am frustrated when progress is over-stated.

I do feel that papers addressing these problems were well-represented at NEUDC (in spite of there being only one session); but perhaps the diversity of themes that they fell under speaks to the “bricks-but-no-structure” problem that you mention. I agree also that we are a long way from the next real step, of understanding how policies need to be combined and layered so as to systematically and sustainably get at the heart of these issues.