The NEUDC conference gave a great overview of the new research on education in developing countries. A remarkable and extensive set of papers focused on the supply side of education, including teachers, school construction, management practices, and factor misallocation. Several papers also studied the demand side of education. These papers dealt with the long-term effects of RCTs and CCTs that had been implemented a decade ago.

Teachers are inarguably at the core of a human capital production function

In an impressive data collection effort, Torsten Figueiredo Walter visited the Ministry of Education websites from across the world to create a global school-level dataset. Using data from over 70 countries, the author found a strong negative correlation between average school-level pupil-teacher ratios and a country’s per capita income. The author also finds high within-country variation in pupil-teacher ratios, a result that suggest that teachers may be misallocated across schools in developing countries.

Getting incentives right

While the previous paper does not reveal why teachers are misallocated, a possible explanation could be incentives. In this line of research, Isaac Mbiti et al. study what kind of teacher performance pay programs are most effective in increasing students’ learning. Using a field experiment in Tanzanian public primary schools, the authors compare the effectiveness of two different teacher incentive systems on early grade learning: a pay for percentile system and a system that rewards teachers based on student learning. They find that both systems improve student test scores and in similar magnitudes.

Teachers might not show up for class

David Jaume and Alexander Willén find that teacher strikes in Argentina lead to lower schooling, lower earnings, and higher unemployment. The educational effects even persist to the next generation.

Whether or not teachers go to school matters a great deal. Emmerich Davies argues that one explanation for variation in absenteeism is the differential attention politicians pay to public services over the cycle of their tenure. Indeed, the author finds that teacher absenteeism decreases substantially in election years, suggesting that political control of the bureaucracy has a strong effect on service provision and bureaucratic performance.

The link between management practices and school productivity

However, it’s not only teachers that matter for learning. Daniela Scur et al. find that in the case of India, management quality in public schools is low on average. Private schools have higher management scores, especially better people management skills, which is consistent with measures of personnel policy, such as teacher pay and retention policies. Moreover, the private-public school gap in student value-added is largely accounted for by differences in management practices.

The long-term effects of schooling supply

Kleemans et al. study the long-term effects of the school construction program by the Indonesian government in the 1970s, finding stark gender differences in outcomes. Women benefit from the program in terms of increased schooling and better labor market outcomes, but less than men. However, the daughters of these women seem to be benefitting more than their sons.

Schooling supply matters also in terms of how schooling is organized. In the context of Brazil’s 2006 compulsory schooling reform, Hanbyul Ryu et al. find that, among students who entered primary school one year earlier, those without any preschool education experienced larger increases in their fifth-year test scores compared to students who gained an additional year of primary education at the expense of preschool. That is, earlier school entry age was better for the children, who would have not otherwise gone to preschool.

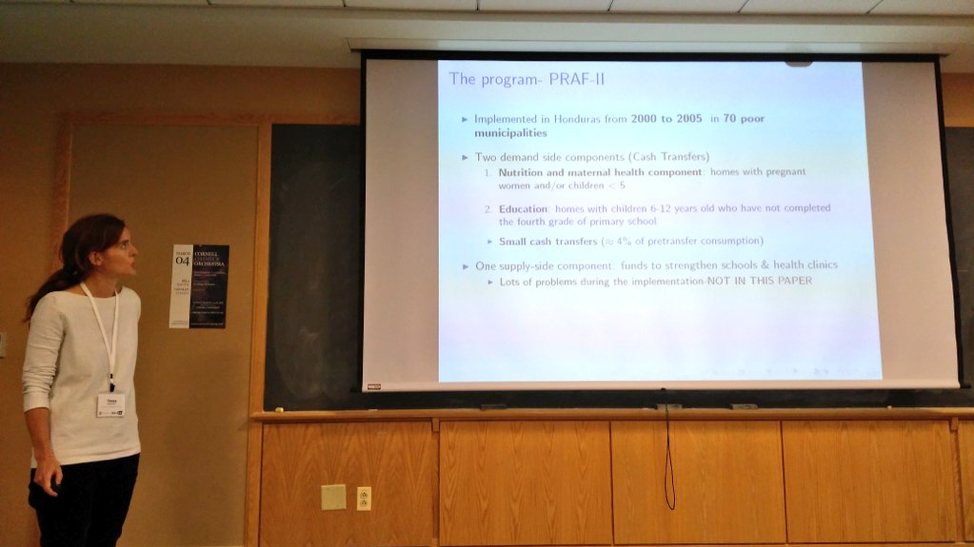

On the demand side of schooling: CCTs and scholarships

Molina Millán et al. found positive educational effects of a CCT in Honduras after 13 years, including on university enrollment, but unfortunately with much lower effects among the indigenous population. Barrera-Osorio et al. showed 9-year follow-up effects of a scholarship program in rural Cambodia, finding that merit-based scholarships were more successful than need-based scholarships, but both had positive impacts. Moya et al. find that in Colombia, a national merit and need based scholarship had a substantial effect on test scores at the top of the distribution.

Not only who you learn from, but also who you learn with matters for educational outcomes

Peer effects are not always as rosy as your golden memories of college friendships. Using a regression discontinuity design in class assignment in a flagship university in Brazil, Ribas et al. find that when your peers are better than you, it increases your willingness to switch careers and reduces the likelihood of having a more prestigious occupation. Similarly, Zarate finds that higher-achieving peers reduce the academic performance of lower-achieving students in Peruvian boarding schools. Roy finds evidence of social tension and non-cooperation among undergraduate peers in a field experiment in India, in which only poor students are incentivized.

Let’s not forget how important the first 1000 days of life are

In a field experiment in Bihar, India, Heeseman et al. find that parents can be taught to teach their toddlers, which can result in higher cognitive capacity. The results indicate however, that cross-productivity with nutrition matters for cognitive skill development. Given how strongly early life should matter for later life outcomes, we are hoping to see a follow-up study of this RCT a decade from now.

Check out also Tarana Chauhan’s post on South Asia (earlier in this series) for two more education papers presented at NEUDC.