What is the relationship between economic and psychological wellbeing? Does our sense of our own power over our actions have ancestral roots? What explains the underrepresentation of women in management positions? These and several other questions were tackled in the presentations related with Behavioral Economics at NEUDC.

Economics and psychology

M. Alloush aimed to disentangle the relationship between economic and psychological wellbeing in South Africa, using data that tracks households from 2008 to 2014. He finds evidence of impacts in both directions. On the one hand, psychological wellbeing affects economic wellbeing: depressed individuals tend to have lower incomes. But at the same time, economic wellbeing affects psychological wellbeing: earning a higher income tends to decrease depression symptoms. These effects were especially pronounced among the poor. (Paper)

On the origins of beliefs, learning strategies, and biases in policymakers

Why do some people believe their own actions determine their outcomes, while other people believe their outcomes are mostly determined by external factors? This is the question Phillip Ross aimed to tackle. By using an instrumental variables approach, he finds that that these beliefs (known as the “locus of control”) have origins in ancestral control over the means of subsistence. Intuitively, societies where subsistence depended on external events (like agricultural societies that depended on rainfall) tend to have a lower locus of control, and these beliefs were transmitted across generations over time. (Paper)

How should farmers learn when faced with multiple input choices? To tackle this multidimensional question, Srijita Ghosh focuses on two learning strategies: a producer can learn by observing the productivity of different combinations of inputs, or the average marginal productivity of each input. The author finds that the best learning strategy depends on how certain the farmer is about his beliefs: when the farmer has a high degree of uncertainty, the optimal strategy is observing an average, while the opposite is true for low levels of uncertainty. (Paper)

What about policy makers? In ‘How Do Policymakers Update?’ Eva Vivalt et al. run a field experiment in international development banks to understand better how policy makers take into account the findings of research, particularly, whether they change their baseline beliefs based on new findings. Indeed, receiving new information changed the prior beliefs of the policymakers, however, the authors also find that policymakers neglect to consider the uncertainty surrounding the results of studies. (Paper)

Behavior change, incentives and contracts

Using a field experiment, Eilin Francis offered micro-entrepreneurs in Malawi two payment plans to purchase solar lamps (an important production input since a large share of the population is not connected to the electricity grid). They could pay on a weekly basis or pay the full amount once and for all at the end of the experiment. The author found a high demand for the plan that involves weekly payments (and not the lump sum amount). Why? Two possible explanations are that entrepreneurs don’t have access to a secure way of saving money, and/or that committing to the weekly payments is a way of acquiring self-control. By providing some entrepreneurs with access to a secure way of saving funds, the author shows that demand for self-control rule is large. (Paper)

With similar research questions in mind, Ariel Zucker et al. used a field experiment in India to compare the effectiveness of two different schemes to incentivize walking. Under one scheme, as long as the participants reached their daily walking goal, they would get payed at the end of the day. Under the alternative scheme, the payments would accumulate, and participants would get the reward at the end of the experiment as long as they didn’t miss their walking goals. Which one worked better? Turns out more frequent payment didn’t make the program more effective, while the second incentive scheme made the program comparatively more cost-effective. (Paper)

Gender differences in the labor market

Can behavioral economics shed light as to why are women underrepresented in the workforce?

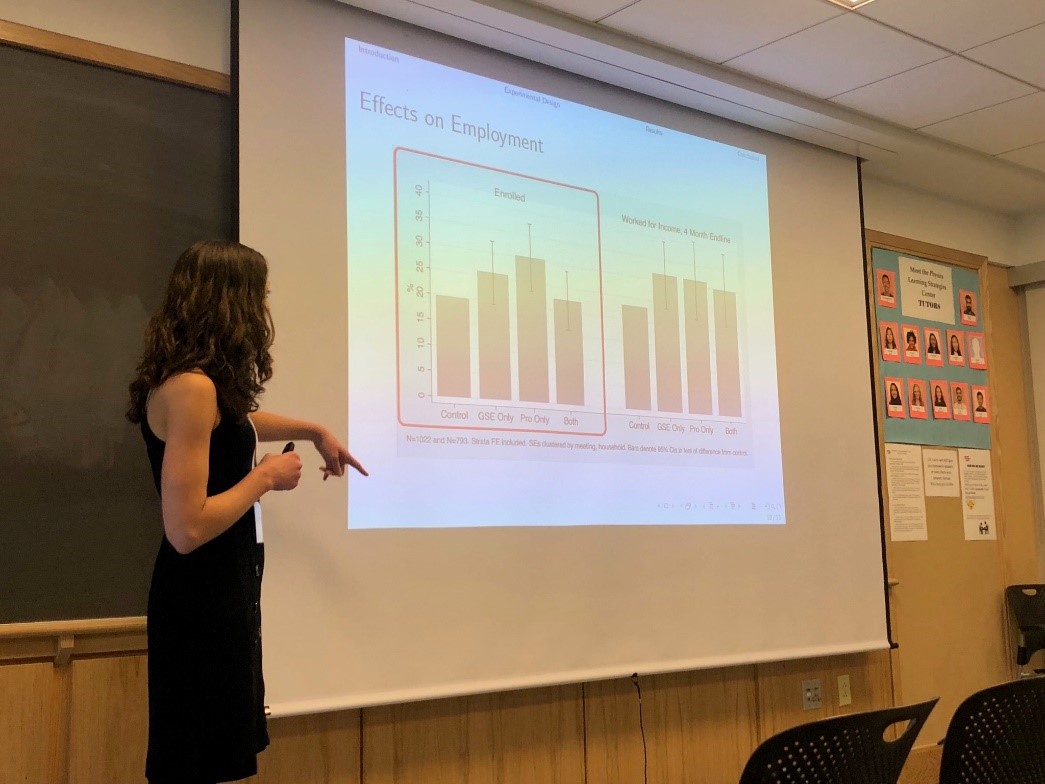

In one of two papers that tackled gender issues in the labor market, Madeline McKelway used a field experiment in India to uncover the relationship between confidence and employment opportunities. In this context, confidence is measured as the beliefs in our abilities to attain our goals (also known as “generalized self-efficacy”). To exogenously boost confidence, the author ran a workshop where the participants received a psychosocial intervention. The author found the increase in confidence made women more likely to become employed, and the effect was both large and persistent. How? Turns out confidence made women more perseverant, and made them exert more effort in achieving their employment goals. (Paper)

But what about female underrepresentation in the top of the job hierarchy? Ketki Sheth et al. used a lab experiment in Ethiopia to understand whether workers behave differently towards their boss if it’ a “she” instead of a “he.” The authors indeed find that workers discriminate female leaders: the participants were more likely to follow the advice of male leaders compared to female ones, which caused female leaders to perform worse. This result shows that discrimination against female managers by their subordinates is indeed an important constraint for women in management positions. (Paper)