South Sudan is currently one of the most food insecure countries in the world, and a current crisis there is making matters worse. In response to an urgent request for food assistance, a recent White House statement on the situation in South Sudan read “Today, the United States will initiate a comprehensive review of its assistance programs to South Sudan. While we are committed to saving lives, we must also ensure that our assistance does not contribute to or prolong the conflict.”

The tragic, complex situation in South Sudan and the White House statement raise an important policy question. Does food aid cause (or causally prolong) conflict in countries that receive this form of assistance?

Unfortunately, obtaining a rigorous answer to that question is difficult. It’s true that the countries receiving more aid have more regular conflict, but this could just be because aid is directed specifically to conflict-affected places. Unless food aid is randomly given out to some countries and not others, a correlation between conflict in recipient countries and aid flows does not necessarily mean that aid causes or prolongs conflict. This challenge has led to a search for natural experiments in which food aid allocations have increased or decreased for reasons unrelated to conflict.

In a 2014 American Economic Review paper, likely the most cited paper proposing to empirically demonstrate a causal connection between food aid and conflict, Nathan Nunn and Nancy Qian (hereafter NQ) proposed a clever idea to try to pin down whether food aid causes conflict. Suppose the US government purchases more wheat grain in years in which the US produces more wheat, either to maintain a price floor or because extra supply drives the price down making it easier to buy more with a fixed budget. If wheat production follows a random process driven by weather in the US or other exogenous, stochastic processes, this pattern would create random variation in the quantity of wheat the US government has available to ship as aid.

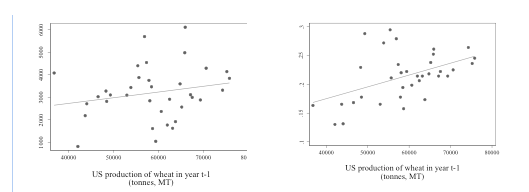

NQ explore this relationship in 1971-2006 data on wheat food aid (hereafter, just ‘aid’) shipments, US wheat production and conflict abroad. Figure 1 below shows the basic argument. In the year after relatively high wheat output, more aid was distributed and there was more conflict around the world. In the terminology of econometrics, wheat production is an instrumental variable (IV).

The immediate problem with the simple version of the instrument is that annual US wheat output varies only in time series, not across the 126 countries in the data. So we only get to “run the experiment” 36 times, once for each year in the data. Recognizing the risk of omitted variables bias and searching for greater statistical power, NQ try a strategy known as a Bartik or shift-share instrument, interacting the frequency of a country’s receipt of US aid over the sample period with the US wheat production level to vary the intensity of countries’ exposure to year-specific wheat output shocks. The underlying hypothesis is that any random variation in extra aid available goes to frequent aid recipients and not infrequent ones. Comparing the conflict experience of regular and irregular recipients could remove all the effect of non-aid conflict drivers, leaving only the effect of aid.

So does this strategy work? As our recent paper shows, unfortunately no. Here we explain the basic problems in a hopefully-intuitive way. In a soon-to-follow companion post, we explain the econometric problem in a bit more detail, drawing on several other recent working papers that shed light on the methods.

The idea behind the NQ strategy is that irregular aid recipients are a quasi-“control” group that allows us to know what would have happened to conflict in a given year to a country that doesn’t receive aid. Figure 2 below highlights what is implausible about this strategy while illustrating the value of plotting the trends in the underlying data as an initial exploratory exercise. Both aid and conflict are heavily concentrated among the countries that regularly receive aid. The 50% of countries receiving little or no aid don’t tell us much about the other factors that cause conflict, because those countries don’t experience much conflict.

The NQ strategy treats variation within years and across countries as the causal experiment. To investigate the role of this variation against trends, we try a new method to demonstrate the role of aid allocations across countries within years on the results NQ report. Holding wheat production in a year and the identity of countries who receive any aid constant, we randomly reassign the quantity of wheat aid distributions and re-estimate the NQ strategy. If extra aid is the channel through which wheat production in the USis causally related to conflict, we should find that in the cases where aid is reassigned to infrequent recipients , the sign of the estimated relationship between aid and conflict should flip to negative. Instead, we find that only 1% of the randomized draws return a negative estimated relationship. This tells us that any strategy relying on variables that vary only by year and not among countries that receive aid does not add any experimental value. If we hold years and the status as a “regular aid recipient” constant, we would find a positive connection between aid and conflict almost no matter how aid is actually distributed.

The general take-away from our paper is that while the Bartik/shift-share IV method can sound compelling, it does not establish a causal relationship between food aid and conflict. Given the trends we observe, it’s likely that comparing relationships between food aid allocations and conflict in these data will only ever tell us that both conflict and aid were higher in the 1980s and 1990s than in the 1970s and 2000s. This might be a clue in the debate about the relationship between food aid and conflict, but any of several phenomena of the 1980s and 1990s (the end of the cold war, higher real interest rates in the US, shifting climate patterns), could generate these correlations without a causal effect.

For applied econometrics students, the lesson is that there is no substitute for plotting your data to identify where your variation comes from, and thinking carefully about the likely direction of selection bias in the simple OLS estimates before believing that IV estimates represent an improvement.

When looking for policy lessons, we are skeptical that withholding food aid commitments is justified from the fact that conflict and US wheat production are correlated. More research is needed, ideally combining solid contextual knowledge of aid allocations with contextual understanding of the places where aid is distributed and conflict occurs. Recent studies covering the Philippines, Iraq, and Afghanistan demonstrate that the mechanisms linking aid and conflict can be contradictory, suggesting that the average effect may be highly context specific. In the meantime, we can be certain that crises in places like South Sudan threaten lives and livelihoods. The decision to cut off food aid should consider not only the still poorly understood risk of conflict but also the cost of not acting.