Supporting food security among undernourished populations has demonstrated returns in terms of reducing income deficiencies of households (Bishop et al 1996), so as to prevent the poor from slipping further into poverty. But should food security legislation follow a targeted approach or aim for universalization? Identification of the poor, for the purpose of targeting benefits, is difficult and expensive, especially in developing countries. Universal inclusion, on the other hand, is easy to administer and has been found more cost effective (Dutrey 2007), despite a popular belief to the contrary. However, there is little empirical evidence available regarding relative redistribution effects of targeted versus universal food security programs. Hence, the debate over the question of the ideal design of a food security program persists.

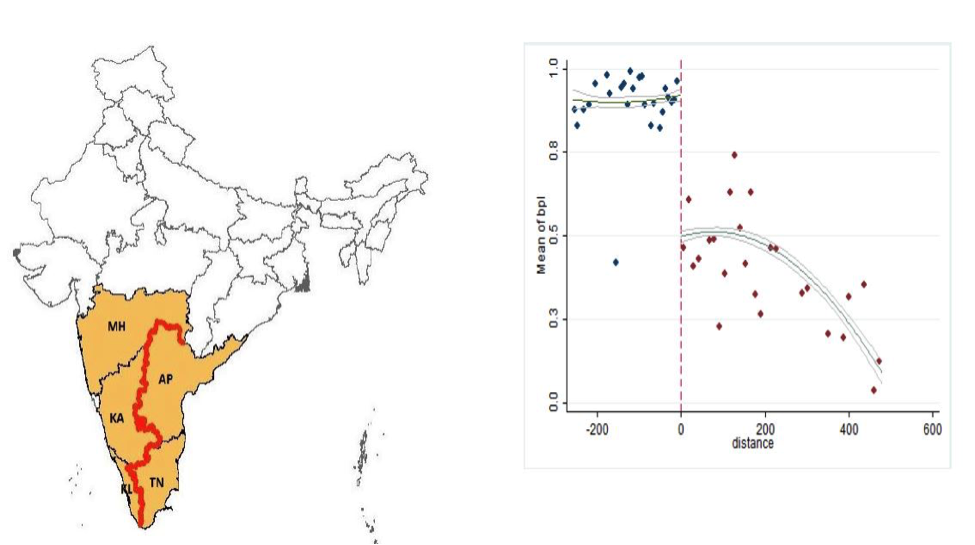

I address this question in my research paper in the context of the world’s largest food security program, the Indian Public Distribution System (PDS). The PDS provides grains at highly subsidized rates to the poor, and the extent of targeting differs from state to state within India. For categorizing universal and targeted PDS states, I employ the ‘middle-class’ definition in Vanneman & Dubey (2011) and term the system in a state to be `more generous’ (as a proxy for a universal food security program) if the income exclusion cutoff is above Rs. 27,235 per annum. In South India, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh run a nearly universal PDS while in the neighboring states it is strictly targeted. Poor households are provided a document called a BPL (Below Poverty Line) ration card that they can use for the purchase of essential commodities from PDS shops. The proportion of BPL ration card holders jumps discontinuously at the long border between Southeastern (Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh) and Southwestern (Kerala, Karnataka, Maharashtra) parts of the country (see figure). This provides an ideal quasi-experimental setting in South India to analyze the impact of universal versus targeted food security programs on vulnerability to poverty using a fuzzy geographic regression discontinuity.

What is the impact on poverty?

My results suggest that living in a state where the PDS is nearly universally applied reduces the average household’s probability of becoming poor within the next year by 9% as compared with a household living in a state where PDS is strictly targeted. This translates into a significant impact on poverty of 50% over the mean. The impacts are larger for more marginalized groups; a more generous PDS leads to a reduction of household vulnerability of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (official designations given by the Government of India to various groups of historically, socially and educationally disadvantaged people in India) by 12%, which translates into a reduction in poverty of 57%. I also decompose the impacts of the generosity of PDS on vulnerability to poverty by occupational groups. A more generous PDS leads to a reduction of household vulnerability of landless non-agricultural wage laborers, landless construction workers and automobile drivers by 12%, 37%, and 26%, respectively. The impacts are larger in occupations concentrated in urban areas, suggesting that urban areas provide access to infrastructure facilities and other opportunities that complement the effects of the food subsidies.

How is poverty impacted?

I find that households use the subsidy from the PDS to make significantly larger investments in various types of risk averse resources, such as increasing their asset base or investing in property and livestock. As Banerjee and Duflo (2011) observe, decisions to save require a certain amount of self-control from rich and poor alike. However, while the rich have a variety of tools at their disposal, like banks and financial advisors, to aid them in the process, the poor have a much harder job to do with their limited resources. Hence, investing in relatively illiquid assets, like livestock, durable goods, property, etc., makes it easier for the poor to forgo ‘temptation’ spending (like alcohol, cigarettes, tea, snacks) and force them not to be ‘myopic’ about the future. A more generous PDS seems to be aiding in the process of resource allocation towards these relatively low-risk investments, which in turn is protecting the poor from shocks in income, and hence reducing their vulnerability to poverty. Households also increase their labor supply in their primary occupation and reduce the number of casual jobs they take up, thereby reducing variability in income and making them less vulnerable to poverty.

Why is poverty impacted?

We can decompose the total improvement of universal over targeted system as follows: Average of a) people under the income cutoff covered under both systems but better off under universal system (because they are taking up more rations due to less stigma presumably) + b) people under the income cutoff who get excluded under a targeted system due to targeting errors, but get the benefits under a universal system + c) people above the income cutoff who wouldn’t be eligible for a BPL card under the targeted system but get the benefits under a universal system. The first is the impact at the intensive margin, while the latter two are the impacts at the extensive margin. I find that the intensive margin effect (a) is 5%, while the extensive margin effect (b+c) is 12%. This suggests that the bulk of the effect is coming from giving more people access to the program rather than better/more reliable benefits under the universal system. Thus, universal inclusion under a food security program might be the way forward for developing countries.

Implications for policy

Currently, the primary concerns regarding a more universal welfare program are whether it would be as redistributive as a targeted program and also as cost effective. My research provides evidence that a more universal approach is more welfare enhancing in the context of the world’s largest food security program. If taken seriously, the results justify expanding the reach of food security support as a necessary means of income support and social protection for the poor in India as well as other developing countries. Finally, there is the question of the viability of sustaining a near universal food security program in the long run. A simple back of the envelope Cost Effectiveness Analysis shows that the cost of reducing the absolute number of the poor by one household through a universal PDS is $89. Supporting local food production and development of better infrastructure facilities may be the first building blocks on the road to realizing the right to food for the poor.