Tanvi Rao is a PhD candidate at Cornell’s Dyson School and a TCI Scholar; she is currently on the job market.

Providing information on the returns to education in the labor market is seen as a powerful demand-side tool to encourage human capital accumulation. Jensen’s influential study in 2010 found that eighth-graders in the Dominican Republic substantially underestimate the returns to secondary schooling and significantly increase their schooling attainment upon receiving information on measured or “true” population returns. An information intervention of this type is attractive to policy-makers, in part because it is demonstrably cost-effective.

However, more recent studies have found that information interventions based on returns have small, statistically insignificant impacts on education outcomes on average, or that only some sub-groups change behavior on account of receiving information (Loyalka et. al. 2013, Fryer Jr 2013, Avitable and De Hoyos Navarro 2015, Bonilla, Bottan and Ham 2016). The existing literature focuses on binding constraints on behavior, such as credit constraints, to explain why certain groups of individuals may not act on newly acquired information about the returns to education, suggesting that if constraints on action do not bind we should see large effects of such information interventions.

In my job-market paper I examine the impact of population earnings information on post-secondary education decisions, as made by students presented with hypothetical choice-sets. Affordability and academic eligibility constraints do not bind on final outcomes measured. Yet, information has small average impacts on stated intentions. Here, I conclude that low average effectiveness is mediated by highly heterogeneous updating of own-earnings beliefs in response to information on population earnings.

The Experiment

In 2014-2015, I conducted a framed field experiment with 1,525 12th grade students drawn, in equal numbers, from 9 government schools in the East Indian state of Jharkhand. Within school, students were randomized into groups of 15, half of which were randomly assigned to participate in an information session following the collection of baseline data. The information session was roughly 20 minutes long and discussed recent government data on population earnings conditional on four post-secondary alternatives and gender. At the end of the session, students took home a sheet that summarized the information. The four post-secondary alternatives specified in all students’ choice sets were: three “enrollment tracks” (technical/professional degrees; general academic degrees; vocational courses/diplomas) and a fourth option of not enrolling in further education. The three “enrollment tracks” were chosen to maintain consistency with the most disaggregated level at which the Indian government collects data on post-secondary attainment and earnings.

At baseline, I collected socio-economic data and measured students’ non-pecuniary and pecuniary beliefs conditional on hypothetically choosing each of the four post-secondary options. The subjective belief of primary interest here is the one the information treatment manipulates—i.e. what students think they would earn, per month, on average, if they complete post-secondary training of type X or if they do not study past high school. To measure students’ information sets about earnings as separate from beliefs about their own earning potential, I also asked them what they think an average person in the population with each type of higher education earns. Apart from data on beliefs, I elicited subjective probabilities of choosing each of the four post-secondary options. Finally, all students took home a “loan card” that asked them about their intentions to borrow for higher education.

For each group, round two of the survey took place one day after round one. Here, I again measured students’ own earnings beliefs, their subjective enrollment probabilities, and recorded their answers to questions posed on the “loan card”. To prevent information spill-overs, both survey rounds for control group students were completed before the treatment group survey started.

Additionally, we stratified the sample by students’ current subject stream—Arts/Humanities, Commerce or Science. In India, subject stream in high school strongly predicts post-secondary education options. Because students are selected into high school streams based on earlier test-scores, the streams serve as a good summary measure of socio-economic status. Entering the Science stream requires the highest scores, followed by Commerce and then Arts.

What I Find

Prior to the treatment, students are misinformed about population earnings. Contrary to expectation, a substantial majority overestimates earnings for all four alternatives, though the extent of overestimation is larger for the three post-secondary tracks as compared to “non-enrollment”.

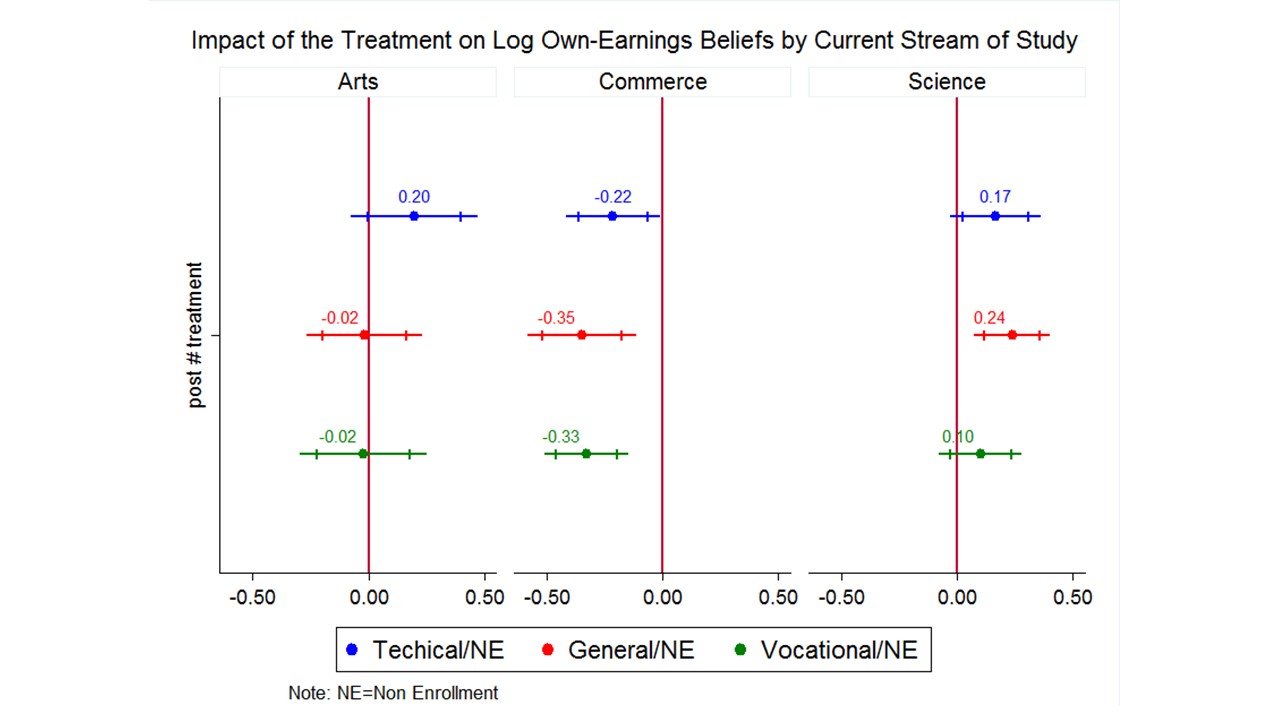

Upon learning that earnings are actually lower than believed, students update beliefs about their own-earnings in a heterogeneous manner, with the average impact being small and statistically insignificant. Arts students do not update own-earnings beliefs, nor do they update enrollment intentions. Unlike other students, own-earnings beliefs for a track is not a statistically significant determinant of intended enrollment in the track for the Arts students, even at baseline.

Students in the Commerce stream respond only to information on the three “enrollment tracks”. They revise earnings beliefs downwards for these three tracks and do not update “non-enrollment” beliefs. As shown in the figure, this pattern carries over to enrollment being relatively less attractive, to these students, post-treatment.

In contrast, Science students only respond to information regarding “non-enrollment”. They revise earnings beliefs downwards for this track only, which, post-treatment, translates into enrollment being relatively more attractive to them.

Within each sub-group, revisions in enrollment intentions are small but statistically significant and in line with the direction of earnings-beliefs. Commerce students are more likely to “not-enroll” and Science students are less likely to “not-enroll”. The average impact of the treatment on borrowing intentions is positive, economically important, and driven entirely by Science students, who are around 15 percentage points more likely to borrow than their control group counterparts.

What Explains the Updating Pattern?

Two conditions are necessary for an individual to update beliefs about their own earnings in response to information on population earnings: (1) the information should be new and (2) the individual should consider the population-level information as relevant to herself. At baseline, Arts students make much smaller errors for all four tracks with regards to beliefs about population earnings than the other two groups. Therefore, non-updating on their part is consistent with the observation that, on average, information provided was a lot less “new” to this group.

However, this does not explain the differential track-specific updating between Commerce and Science students. Both groups make identical baseline errors for all four tracks, highlighting the importance of differential relevance of track-specific information. Suggestive evidence supports that this pattern is Bayesian: individuals with stronger likelihood to pursue a track are less likely to update earnings beliefs for that track, consistent with them having less dispersed priors for this track. Commerce students are at baseline less likely to attend post-secondary education and respond more to information on the three “enrollment tracks”, while the opposite is true for Science students. However, in the absence of data on the variance of individuals’ prior beliefs, I cannot rule out that a portion of track-level non-response may also deviate from the Bayesian benchmark. Some insights from recent literature (Wiswall and Zafar 2015) reveal that non-response is to be taken seriously: a fifth of their sample is comprised of “Non-Updaters”, and a substantial portion of their sample is more “Conservative” than their Bayesian benchmark would predict.

Implications

These findings indicate that the heterogeneous nature of the process by which individuals apply population-level information to their beliefs and intentions is important. Investigating this process is important for designing effective information campaigns. Additionally, to the extent that non-response to a particular piece of information may deviate from what the Bayesian model predicts, careful experimentation with content, delivery, and framing of information of this type is required.