In a recent UNU-WIDER project Gary Fields, Guillermo Cruces and Mariana Viollaz and I undertook an extensive analysis of the nexus between economic growth, employment conditions and poverty during the period 2000-2012 for 16 Latin American countries. We prepared 16 case studies (one for each country) and one cross-country study that have been sequentially published recently as WIDER Working Papers (the series of 17 papers can be found here, and a video of the presentation at the UNU-WIDER 30th anniversary conference can be found here). We were looking for answers to some questions that have long been present since the very first days of development economics: Has economic growth resulted in gains in standards of living and reductions in poverty via improved labor market conditions? How do the rate and character of economic growth, changes in the various employment and earnings indicators, and changes in poverty and inequality indicators relate to each other?

When economic growth takes place there has to be some channel for it to contribute to poverty reduction, e.g. improvements in employment conditions or implementation of social programs (such as conditional cash transfers). In our research, we examine the employment channel. Employment includes not only wage and salaried employment but also self-employment. Also, the issue is not simply whether people are employed, but also how much they earn for the type of work that they do. Thus, besides investigating employment/unemployment per se, we also explore the effects of economic growth in job categories/types and labor market earnings.

Our contribution is an in-depth study of the multi-pronged growth-employment-poverty nexus based on a large number of labor market indicators (twelve employment and earnings indicators and four poverty and inequality indicators) for sixteen Latin American countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Honduras, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, El Salvador, Uruguay, and Venezuela). We directly relate changes in all labor market indicators to economic growth, and changes in all employment and earnings indicators to changes in poverty. We use data from nationally representative household surveys from the SEDLAC-Socio-Economic Database for Latin America and the Caribbean (CEDLAS and the World Bank 2014). The microeconomic data used in this project included more than 150 household surveys, comprising observations for 5 million households and 18 million people.

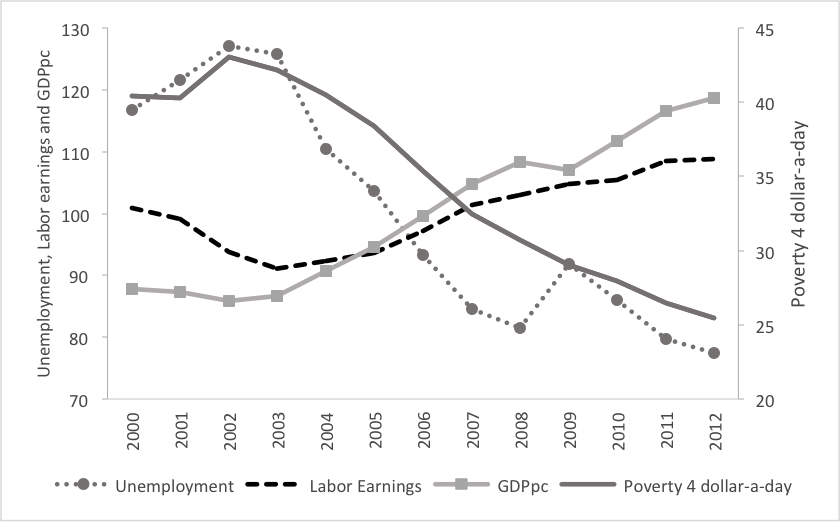

We find remarkable progress in all three aspects of the growth-employment-poverty nexus (see Figure 1):

Growth: National income accounts reveal that all sixteen countries achieved positive rates of annual growth of real GDP per capita during the 2000s, ranging from 1 per cent a year in the case of Mexico to 5.6 per cent a year in the case of Panama and Peru. The regional average (unweighted) for the sixteen Latin American countries was just under 3 per cent, well above the annualized rate of growth of GDP per capita in OECD countries, which was 1.0 per cent a year.

Labor market indicators: The rate of improvement in labor market indicators in Latin America was exceptional. All 16 of the labor market indicators used in this study improved in Bolivia, Brazil and Peru, 15 of the 16 improved in Panama, and the majority of the labor market indicators improved in all of the other countries except for one (Honduras).

Poverty rates: Using the 4 dollars-a-day poverty line (‘poverty’) and the 2.5 dollars-a-day poverty line (‘extreme poverty’), we find reduced rates of poverty and extreme poverty in fifteen of the sixteen countries. On average, extreme poverty fell 45 per cent while poverty declined 37 per cent. Once again, Honduras was the only Latin American country to have registered an increase in its rate of poverty.

Figure 1: Changes in GDP per capita, poverty and selected labor market indicators

In short, the 2000s were a time of strong improvement in the growth-employment-poverty nexus in Latin America. The only exception to this pattern was Honduras, which was simultaneously affected by the international crisis and episodes of political instability.

In the great majority of Latin American countries, economic growth took place and brought about improvements in almost all labor market indicators and consequent reductions in poverty rates. But not all improvements were equal in size or caused by the same things. To understand why some countries progressed more in certain dimensions than in others, we performed a number of additional analyses, from which we draw the following lessons, detailed below:

- Looking across countries: Growth was associated with improvements in labor market indicators, but the relationships were weak (not tightly correlated).

- Looking across countries: Some macroeconomics factors played a key role in improving labor market conditions in some countries, although they were absent in others. The single most important factor was the commodity boom during the 2000s that benefited most countries in South America. However, other countries like Panama and Costa Rica did not enjoy it but were equally successful in improving labor market conditions.

- Looking across countries: Improvements in employment and earnings were clearly associated with reductions in poverty.

- Looking at year-by-year changes within countries: When economic growth was faster, employment and earnings indicators and poverty and inequality indicators improved more rapidly. Additionally, as labor market conditions improved, poverty was reduced. However, the magnitude of these effects and the patterns over time varied substantially from country to country.

- The patterns of changes in labor market earnings were strongly progressive: In most countries the changes in labor earnings in percentage terms were larger for the poorer deciles.

Overall, the growth-employment-poverty nexus in Latin America during the 2000s changed much more favourably than was the case in the OECD countries in general and the United States in particular. It would be interesting to know about developing economies in other regions of the world. Such studies define the current research frontier.

The post-2012 period seems to be marked by more heterogeneous country experiences than the 2000-2012 period analyzed in this project. Countries from South America are facing the challenge of achieving economic growth without the tailwind of the commodity boom that took place at the beginning of the century. While policies to achieve economic growth are being put into place, the channels to improve employment conditions and social programs should remain open and be enhanced: it is the only way economic growth will help reduce poverty, the single most important objective these countries can pursue.