Pastoralists in arid and semi-arid ecological zones of Sub-Saharan Africa are particularly vulnerable to severe drought, which has repeatedly occurred in recent years. Each drought causes widespread death of livestock, which is the second most important asset for pastoralists after human capital. Without proper safeguards against livestock mortality, pastoralists are easily caught in poverty traps, as the loss of livestock jeopardizes future income generation capacity.

To help pastoralists manage drought risk and protect assets, the International Livestock Research Institute, together with Cornell University and the Oromia Insurance Company, introduced index-based livestock insurance (IBLI) in the Borena zone of southern Ethiopia in 2012. Modeled after the product piloted in Kenya in 2010, IBLI uses the standardized Normalized Differenced Vegetation Index (NDVI) – satellite imagery of rangeland conditions – to construct an index of pasture conditions, and pays out to the insured based on predicted losses when the NDVI dips below a certain pre-determined threshold level.

It has been claimed that index insurance has several advantages over traditional agricultural insurance in reducing moral hazard, adverse selection, and transaction costs associated with verification of individual losses. It also provides vulnerable households with means to mitigate otherwise uninsured weather risk, the most common and crushing of shocks. In spite of these advantages, however, the uptake of index insurance has been disappointingly low, rarely above 30 percent of the intended population, across the several contexts in which it has been introduced. There is, thus, an urgent and clear need to identify constraints that hinder the demand of index insurance.

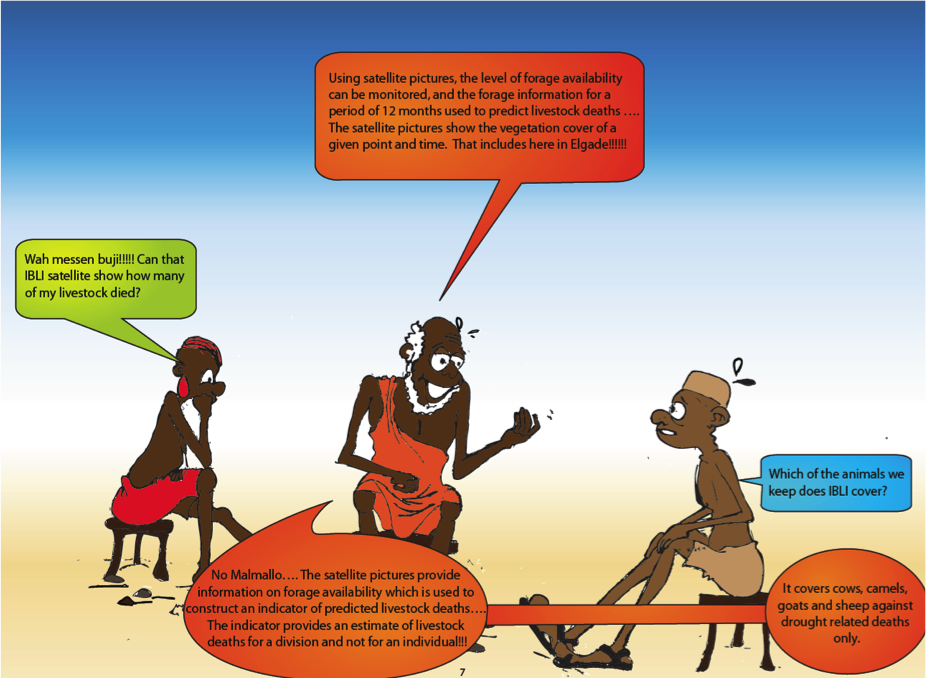

My recent paper in World Development – co-authored with Munenobu Ikegami, Megan Sheahan, and Chris Barrett – tackles this issue by examining the factors that drive (and dampen) the demand for IBLI among pastoralists in southern Ethiopia. We paid particular attention to the lack of understanding about the insurance product, price and risk preferences as potential determinants of insurance demand. To understand the role of each component, we rely on two experiments. The first was intended to improve overall comprehension of IBLI through the random distribution of a “learning kit” – a comic (Figure 1) and an audio tape of a skit. The second experiment was the random distribution of discount coupons, which lowered the cost of purchasing IBLI by 10 to 80 percent. The recipients of these two interventions were selected randomly from the sample we surveyed.

Our data indicate that uptake of IBLI approached 30 percent of our sample in the initial year of product offer, meeting or exceeding that of most other index-based insurance products in their pilot periods. Our regression analysis yields three main findings. First, the learning kits improve understanding of the product, but better knowledge does not appear to consistently increase uptake of IBLI—even though survey respondents reported that lack of knowledge was one of the main reasons for not purchasing IBLI.

Second, consistent with theory, we find that risk-averse households are more willing to buy IBLI. This result conflicts with previous studies that find risk-averse households are less likely to buy index insurance (e.g., here), in part because of basis risk (the difference between the losses actually insured and the losses insured based on index values). If the basis risk is large, potentially due to a design flaw in the product, index insurance can be akin to a kind of a lottery. Our finding that IBLI is more likely to be bought by risk-averse households may reveal that it is properly designed to reach the vulnerable, risk-averse pastoralists that we target, as discussed in an earlier blog post by Nathan Jensen.

Finally, the reduced price of the insurance through the provision of discount coupons significantly increases the uptake of IBLI. While there is a potential threat that a one-time price reduction creates a price reference point that decreases demand in subsequent periods (when the discount coupons are no longer offered), we find no evidence of these price anchoring effects. Thus, it may well be that a provision of a temporary subsidy is an effective tool to boost insurance uptake without persistent (adverse) effects on future demand.

Our study, however, only investigates uptake of the IBLI product in the first two sales periods. Future research ought to confirm our conclusions, by tracking participating households for a longer period of time so that index-based insurance products can be better designed and actualize their potential in reducing poverty among vulnerable pastoral populations.

The livestock market must be support by IBLI to be a profitable business.

I thought it was interesting that to help pastoralists manage drought risk and protect assets, the International Livestock Research Institute, together with Cornell University and the Oromia Insurance Company, introduced index-based livestock insurance (IBLI). This was a great way to equalize the insurance on animals for the farmers. Do you agree that insurance on the livestock matters?

I believe it does, but I am conducting another research on the impact of IBLI on pastoralist livelihoods to assess whether my belief is true. Hopefully I can introduce some results on this page soon!

This is interesting. However, it is not clear if coupons are based on the # of livestock heads or just households.

Thank you very much for your interest. Coupons are distributed to randomly selected households, regardless of the number of livestock they own and herd.