An important number of policy interventions in developing countries today take the form of fixed-term projects. How can we identify whether projects have sustained impact after they end? Measuring “what is left behind” is particularly crucial in the case of cash transfer interventions. Indeed, it is a matter of debate whether cash transfers can lead to long-term impacts, or can help “graduate” beneficiaries out of poverty. Do beneficiaries take advantage of the cash transfers to invest in productive activities and improve their living conditions in the long term? If yes, what happens after the project ends and households stop receiving transfers, especially among the poorest? And what mechanisms possibly allow overcoming existing constraints and facilitating productive investments? These are the questions that motivated me to study the sustained investment impacts of a cash transfer project in Niger 18 months after project termination. This work is joint with Brad Mills and Patrick Premand.

Cash transfers and sustained impacts on productive investments in Niger

There has been a significant rise of cash transfer interventions in Sub-Saharan Africa in the last 15 years. In the context of recurring droughts, the Government of Niger and the World Bank implemented a cash transfer pilot project in the Tahoua and Tillabéri areas between January 2011 and June 2012: 2,281 beneficiary households received small, regular monthly transfers of 10,000 FCFA (approximately 20 USD, or 20% of household consumption) over a period of 18 months. A unique feature of the pilot project is that it encouraged households to setup tontines (local rotating saving groups) to facilitate savings for productive investments.

A major question surrounding cash transfers regards their ability to foster productive investment and raise long-term household consumption beyond the short-term effects observed during the project. Such investments have been found in Mexico by Gertler et al., and also observed in Sub-Saharan Africa (see here and here for instance). However, there is still limited evidence of productive impacts from small, regular cash transfers in Sub-Saharan Africa, particularly after the transfers have ended. Rural Niger, in particular, is one of the poorest areas in the world, where households face multiple risks and constraints, as well as pressing consumption needs.

Measuring impacts 18 months after the end of the transfers

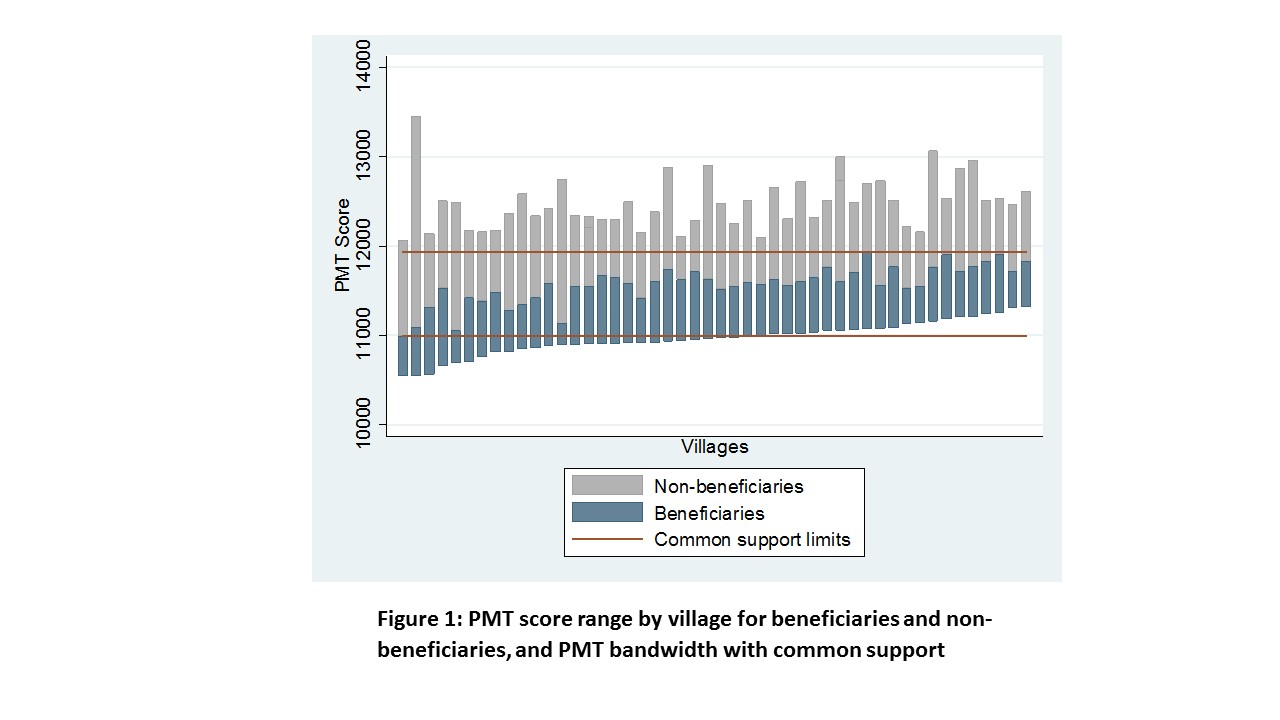

Households in the project areas were first surveyed in 2010 and their Proxy Means Testing (PMT) scores were computed based on socio-economic characteristics. Then, in each village, 30% of households (those with the lowest PMT scores) were targeted and selected as beneficiaries. Beneficiaries then received cash transfers for 18 consecutive months. We conducted a follow-up survey 18 months after the beneficiaries stopped receiving transfers, so 36 months after the baseline, among 2,000 households.

We rely on quasi-experimental methods to estimate sustainability of program impacts on productive investments. Our main identification strategy consists in exploiting the design of the project to compare beneficiary and non-beneficiary households with similar PMT scores. For that, we create a “common support” sample, in which it is possible to find two households with identical PMT scores but different eligibility statuses: one might be a beneficiary in a village A (below the 30% cut-off), while the other might be a non-beneficiary in village B (above the 30% cut-off) (see Figure 1). For households in this common support sample, we use simple difference to infer beneficiary household impacts on variables not included in the baseline. For variables included in the baseline (mostly: livestock and housing conditions), we are able to use difference-in-difference. And for all variables, we conduct several robustness tests by using the full sample, employing village fixed-effects or by conducting the estimations via Propensity Score Matching.

Results: livestock & other investments

Our main finding is that cash transfer recipients have made large investments in livestock. Compared to non-beneficiaries, beneficiary households increased their livestock by 0.3 to 0.4 Tropical Livestock Units (TLU), which is equivalent to about half a cow, or three goats, or thirty chickens. This represents a 50% increase compared to their baseline livestock holding, or an amount of 88,000 FCFA, which is almost half of the amount received during the 18 months of the program. This impact is large, especially 18 months after project termination, but consistent with qualitative evidence from Niger and elsewhere, and also consistent with administrative data from the project on the use of cash transfers.

Among the other dimensions that we considered, we found limited evidence of impact on durables or on housing improvements. We also measure household enterprise variables (small businesses for instance) but did not find any significant impact for beneficiaries. However, we found some positive impacts on agricultural production, in particular higher use of agricultural inputs and higher productivity.

Mechanisms

Several alternative mechanisms can explain our observed impacts on productive investments. For instance, the poverty traps literature suggests that among the poor, cash transfers could help the relatively better-off households cross the critical asset threshold by realizing productive investments. However, small regular cash transfers would not be expected to foster productive investments among the very poor. We test this hypothesis by measuring the heterogeneous impacts of the transfers in our sample of poor households. Interestingly, we find a greater impact of these small, regular transfers on the poorest of the poor, in particular on livestock accumulation and tontine participation. As such, the observed impacts are not consistent with the prediction of our poverty traps model.

Alternative theoretical mechanisms relate to the alleviation of saving constraints in the presence of lumpy investments. We explore the effect of the project on tontine participation among beneficiary households, which was supported by the project. 18 months after the project ended, we find that the percentage of beneficiaries participating in tontines is twice the percentage of non-beneficiaries (20.7% vs. 10.2%). These result suggests that tontines may have been a key instrument for household investment, and that the credit and saving constraints may have been the key constraints alleviated by the transfers.

Policy implications & further research

Our study in Niger presents encouraging results on the potential of cash transfers to stimulate household productive investments. In particular, our results show that even the poorest households, despite pressing consumption needs, are able to invest part of the transfers to increase their productive asset base. These findings suggest that social safety nets in the form of cash transfers may potentially generate long-term improvements for very poor households. They also suggest that there may exist complementarities between cash transfers and the promotion of saving groups to foster investments in productive activities.

However, more research is needed to identify the mechanisms by which small, regular transfers generate a productive impact: particularly, do they ameliorate saving and credit constraints, or the adverse effect of risk? Understanding these mechanisms will help in the design of cash transfer programs to efficiently lift households out of poverty.