Who should have the final say on social assistance program implementation: bureaucrats in the capital city or local communities? Arguments favoring decentralized implementation include lower costs to acquire accurate information about beneficiary needs (Alderman 2002), increased responsiveness to local needs (Faguet 2004), and increased knowledge of what is politically and socially feasible in the local context (Pritchett 2005). Others argue that decentralization worsens service delivery when there is room for political capture by local elites (Bardhan and Mookherjee 2005), preferences of local decision makers are not pro-poor (Conning and Kevane 2002), and monitoring mechanisms are weak or non-existent (Lessmann and Markwardt 2010).

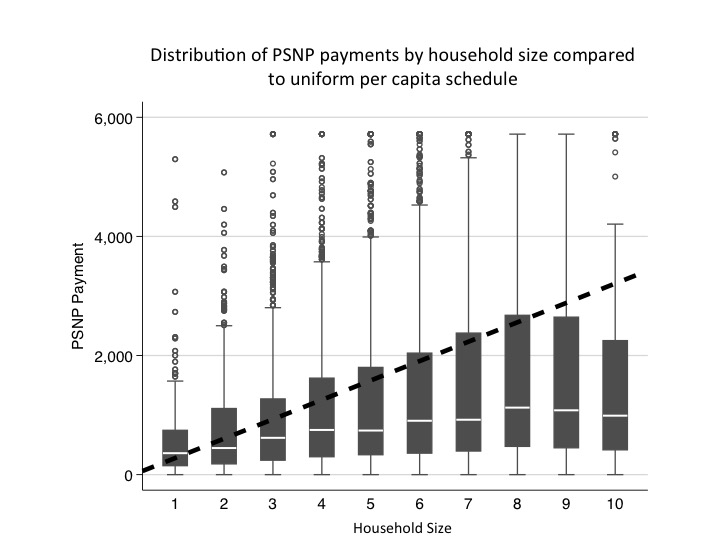

In my job market paper, I examine who wins and who loses from the unintended decentralized implementation of Africa’s second largest social assistance program: Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP). In theory, the PSNP should be implemented strictly using central government rules, including full and uniform transfers per person in an eligible household. In practice, however, communities do not receive enough funding to fully implement the program according to those mandates and, therefore, must use local discretion to distribute aid. With reduced budgets, how do local communities alter implementation?

Recovering local revealed community equivalence scales

In order to empirically examine the distributional impacts of this decentralized approach, we need a rule with which to compare the welfare of households of differing sizes and compositions. This rule must be flexible enough to influence both which households are selected into the program and how much aid they receive. The literature does not provide an adequate rule, so I derive one theoretically based on the principle of revealed preference and develop an empirical method to implement it by extending the technique developed by Olken (2005). Then I use these estimated allocation rules to compare the distributional consequences of how the local governments decided to implement the program with how the central government intended it.

Results

My key findings are:

- Decentralized implementation can lead to pro-poor allocation rules.

- Despite communities’ pro-poor implementation, the program operating with constrained funding does not significantly lower overall poverty rates.

- Based on simulations with a fully funded program, the PSNP reduces poverty under both centralized and decentralized program control, despite different allocation rules.

Ethiopian communities allocate more aid to underprivileged groups with lower wage earnings potential, unlike the uniform allocation rules dictated by the central government. For example, teenaged girls receive about 33% more than teenage boys, working aged women receive about 75% more than working age men, and elderly receive about 40% more than working aged adults. But, when comparing the communities’ pro-poor approach with the central government’s uniform allocation rule—in which the same reduced budget is spread evenly among fewer beneficiaries—the overall poverty rates are neither significantly different from each other nor significantly lower than a counterfactual with no program payments. By contrast, when simulating poverty levels with the intended fully funded program, both the decentralized and centralized approaches reduce poverty measures by approximately the same amount, despite their different allocation rules. The major policy takeaway is that the financial scale of the program is much more important to overall poverty reduction than the locus of control over implementation.

Contributions to equivalence scales and program design literature

The methodological extension to Olken’s (2005) technique for calculating revealed community equivalence scales to include the intensive margin (how much aid) instead of only the extensive margin (whether or not a household is included in the program) contributes to resolving the long standing challenge of defining “socially adequate” consumption levels. Pollak and Wales (1979) argue that traditional demand based techniques of calculating equivalence scales do not adequately deal with the broader question of what communities or societies feel is the “socially adequate” consumption level. One way to recover this level is to observe how communities make the decision for themselves, such as in the Ethiopian context discussed in this paper or in the Indonesian context described by Olken (2005).

Additionally, decentralized implementation can be pro-poor. The case of Ethiopia’s PSNP runs contrary to a large body of research that suggests decentralized program implementation is distributionally regressive (e.g., Reinikka and Svensson 2004; Bardhan and Mookherjee 2006; Galiani et al. 2008; Ricker-Gilbert and Jayne 2012; Lunduka et al. 2013; Kilic et al. 2015).

Contributions to the policy debate over program design

These findings provide practical operational advice for the Government of Ethiopia and other program implementers that fewer resources should be deployed with the goal of enforcing the full and uniform payment mandate. Any additional funds allocated towards the program would be more effectively diverted to simply enlarging the overall program budget, rather than regulating how communities allocate the aid they receive.

Finally, these results suggest that discussions of appropriate budgetary scale should dominate the public debate about social assistance programs, not the debate over implementation modality. Because there is no statistically meaningful difference in poverty rates when comparing centralized versus decentralized implementation in either the reduced (actual) budget scenario or the fully funded (intended) scenario, this means that as the scale of the program grows so does its poverty reducing impacts. This effect holds irrespective of whether the program is implemented according to centralized mandates or local discretion.