Will we continue to produce enough food to feed everyone as our population grows? In his 1798 work, “An Essay on the Principle of Population,” Thomas Malthus pointed out that because populations increase in size geometrically while agricultural productivity increases linearly, we were destined for a future of famine. He hadn’t anticipated the industrial revolution and later the green revolution, which allowed food production to keep pace. But as evidence presented during last week’s 2nd International Conference on Global Food Security suggests, populations continue to rise while agricultural productivity has struggled to keep apace in many regions.

Was Malthus right after all?

In many parts of the world, yields have flat-lined as we’ve exhausted the gains from mechanization and fertilizer use. According to researchers at China’s Agricultural University, crop yields, especially staples such as maize and rice, have stagnated for the past 30 years, and China is projected to import almost half its food by 2050. M.K. van Ittersum of Wageningen argues that in Bangladesh, the combined effect of population growth and coastal erosion may reduce crop yields, particularly maize. The only bright spot is Sub-Saharan Africa, where yields are far below their potential. Dr. Brian Keating of CSIRO expounded on how improvements in data availability allow for comprehensive analyses of soils and climate. When combined with studies of yields attained by the best farmers, this data suggests yields could double or even triple when using modern techniques and fertilizer.

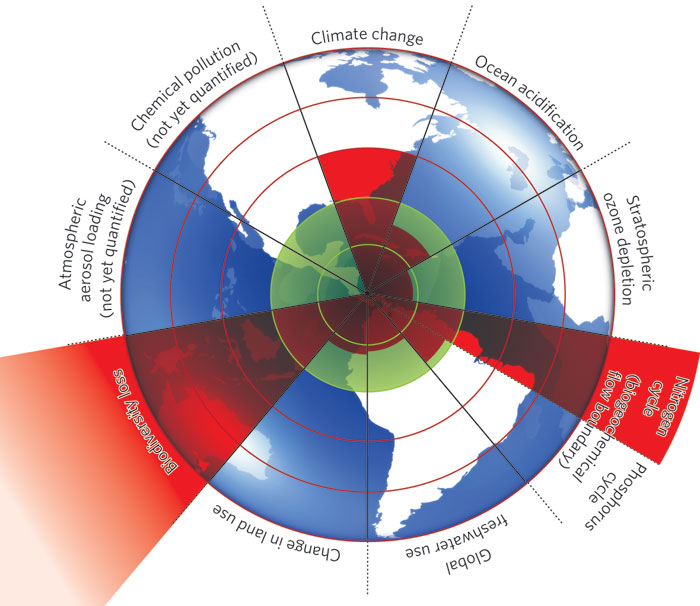

Across most regions of the world, there is a clear need to increase production – and to do so in such a way that negative environmental effects are mitigated at worst and actually off-set at best. As X. Zhang of Princeton pointed out, maintaining the nitrogen balance is key: too little, and crops fail for lack of nutrients; too much, and runoff leads to algae bloom, depriving rivers and oceans of oxygen. The following figure, from Rockstrom’s seminal article in Nature “A safe operating space for humanity,” illustrates that climate change is but one of the several environmental systems where we’ve exceeded planetary boundaries. Indeed, of the three highlighted—biodiversity loss, climate change, and the nitrogen cycle—the latter is by far the most out of kilter.

Offering a spot of hope in this gloomy prognosis, many presenters at the 2nd International Conference on Global Food Security provided research that will help to advance a sustainable intensification agenda, characterized by growing more food – especially nutritious food – while simultaneously reducing adverse environmental effects.

In fact, Uno Wennergren and Usman Akram of Linköping University, Sweden, presented research showing that transporting nutrients (from excretions of humans and animals) from surplus areas to sinks could offset as much as 100% of the fertilizer needed in the nutrient-deficient areas. And, transporting the nitrogen and potassium from these excretions is actually cheaper than transporting mineral fertilizer.

Demand for meat, including beef – a large contributor to global CO2 emissions – is predicted to rise substantially as the standard of living among the world’s poor continues to increase. However, Rafael de Oliveira Silva of the University of Edinburgh and Scotland’s Rural College, UK, demonstrated that intensification in Brazil that combines grassland improvement and reduced feedlot finishing time will actually lead to reduced CO2 emissions. While the situation in Brazil cannot necessarily be transferred everywhere in the world, it does suggest that restoring degraded pasture lands provides an opportunity to both meet increased demand for beef and reduce carbon emissions – a win-win for all (except maybe the cows…).

Finally, in our pursuit of expanding global agricultural productivity, we cannot forget to ensure that farms produce a diversity of crops and incorporate livestock and aquaculture when possible. According to Rachel Bezner Kerr of Cornell University, even poor and vulnerable farmers can use (and are using) agroecological approaches to improve both their food and nutritional security and soil health and biodiversity. There are various approaches to assist farmers in adopting or adapting improved technologies, such as farmer-led learning groups, as Robert Mazur of Iowa State University showed. Similarly, Danielle Niedermaier shared about a program that Peace Corps/Senegal developed called the Master Farmer Program in which local farmers (Master Farmers) develop demonstration and training farms for a variety of improved agriculture and agroforestry technologies. A process evaluation conducted in 2014 found that over 70% of farmers who had been trained by Master Farmers had applied at least one improved technology.

Suffice it to say, Malthus had a great and convincing theory, but we have not run out of ways to continue to prove him wrong. Replicating the successes of innovative farmers and, more importantly, investing in state-of-the-art research and development will ensure that our food supply continues to keep up with demand while protecting the environment essential for the longer term sustainability of our production and consumption systems.

*Updates: Slightly modified versions of this post were released on Danielle Niedermaier’s Medium blog and the Peace Corps’ Passport blog.