The puzzle

Across the world, workers’ wages are positively correlated with the number of years they spent in school. Economists think these returns largely flow through two channels – skill acquisition and signaling. The skill acquisition channel posits that people learn skills in school that are valuable to employers. The signaling channel submits that schooling is rewarded not because it makes students smarter, but rather because it reveals information about students’ underlying ability endowment that employers can’t otherwise observe. How much each channel matters is hotly debated. My job market paper, co-authored with Feng Hu of the University of Science and Technology Beijing, provides new evidence from China suggesting that signaling plays a key role in driving these returns.

The policy experiment

To tease apart the relative contribution of the two channels, we would want to hold either signal or skills constant while varying the other. Consider a policy that increases the amount of schooling it takes to get a credential, the main “signal” of interest for many employers. If skill acquisition matters most, affected individuals would keep years of schooling constant and adjust their highest credential downward (e.g. go from a high school degree to a middle school degree plus three years of high school). If signaling is the main driver of returns to schooling, the policy should induce an increase in total years of schooling but little change in credentials; furthermore, if the second case were true, the extra time spent in school as a result of the policy should have low returns in the labor market.

We study a policy that comes very close to this ideal experiment: in 1980 the Chinese government announced that it would increase by one the number of years needed to complete primary education while leaving unchanged the national curriculum and length of all other levels of schooling. Affected students could either keep total years of schooling constant by forgoing the credential they would have attained in the absence of the policy, or keep credential attainment constant by spending an additional year in school.

Research design

We use a regression discontinuity design to identify the causal effect of the policy on schooling and labor market outcomes, comparing those leaving primary school just before the policy takes effect to those leaving just after. We use documents from China’s national archives to determine when the policy was implemented in each of China’s 345 prefectures. It was rolled out gradually over 25 years, so we can make our before/after comparison at different times in different places while netting out cohort, locality, and cohort-by-region fixed effects that could bias our estimates.

What we learn

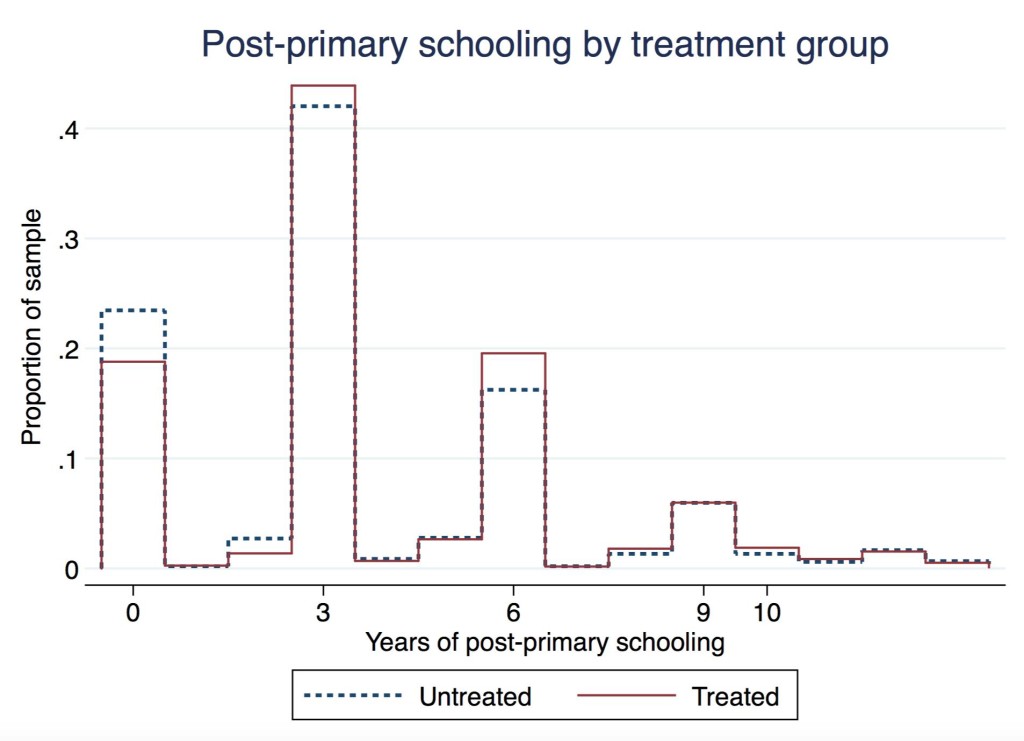

Our results are consistent with the signaling model’s predictions. We find no evidence of a decrease in credential attainment or years of post-primary schooling to offset the extra primary year.

The characteristics of who gets which credential are unaffected, allowing us to estimate the return to an extra year of primary school holding highest educational credential constant.

The characteristics of who gets which credential are unaffected, allowing us to estimate the return to an extra year of primary school holding highest educational credential constant.

These estimates also suggest the importance of signaling. The extra year increases monthly income by 2.03%, which is small compared to the 8-14% per-year premium to earning a credential seen in the same data. Though this small return could be due to the peculiar nature of the extra year, other recent, well-identified estimates of the returns to education from urban China are similar, suggesting a large portion of the returns to schooling observed in the cross-section are likely to flow through the signaling channel. Still, our positive estimates of the returns suggest that affected individuals also acquired skills in this extra year. We see the greatest boost accrue to those with the least schooling, consistent with recent work showing that increased instructional time is an important mechanism behind the success of a group of high-performing New York charter schools in improving outcomes for the underprivileged.

Policy implications

The policy has induced over 400 million individuals to spend an additional year in primary school so far, which translates to nearly a trillion person-hours reallocated from the labor market to the pursuit of schooling. Despite the greater returns for the less-educated, our cost-benefit calculation suggests that the policy was a net fiscal loss of tens of billions of 2005 US dollars.

These results highlight the immense implications of a seemingly arbitrary policy choice: how long should each level of schooling last? We use Demographic and Health Surveys data from 73 other countries to show that patterns similar to what we see in Figure 1, consistent with the dominant role of signaling in household schooling decisions, appear to be a relatively common phenomenon in developing countries. We believe that this policy decision is surprisingly under-researched given the resources at stake.