In September, the United Nations General Assembly intends to adopt one of the most ambitious and comprehensive agendas the international community has ever seen, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Meant to build on the (relative) success of the original eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the SDGs establish 17 new goals with 169 indicators for human, societal and ecological wellbeing that all nations are to strive towards.

Given the aspirational nature of these goals, many are expressing concern over how to execute them. Concerns over the implementation of the SDGs fit in three broad camps:

- A ‘central planning’ approach, reminiscent of Soviet five year plans, will inevitably fail in a complex and dynamic global system.

- The lack of prioritized indicators makes it difficult to focus energy and resources on specific programs and monitoring.

- Such a piecemeal categorization encourages tunnel thinking, avoiding important synergies and tradeoffs (such as how to simultaneously ensure sustained economic growth and de-carbonization).

With these in mind, various bodies have proposed different approaches, each of which has its own strengths and weaknesses.

Solution 1: Regionally and nationally tailored approaches.

Proposed by: The UN Stakeholder Forum

Having orchestrated a long and extensive global consultation process, the forum advocates moving forward with a decentralized approach where stakeholders and policymakers pick and choose which SDGs to prioritize and how to do so. International organizations and NGOs concerned about specific goals can use naming and shaming or the increasingly popular ‘cash on delivery’ model to encourage countries to adhere to specific goals, creating a ‘race to the top’ system of incentives.

- Pros: In addition to its political palatability, such an approach is in-line with emerging evidence that development policy effectiveness hinges on a local rather than global approach.

- Cons: Locally determined priorities and policies defeat the purpose of a universal set of goals, effectively making them redundant by perpetuating the status quo and impeding cross-country comparisons.

Solution 2: Rank SDGs in order of cost-benefit ratio.

Proposed by: Copenhagen Consensus Center (CCC)

In collaboration with a number of prominent economists, including Nobel laureates Finn Kydland and Thomas Schelling, together with University of Chicago professor Nancy Stokey, the CCC has published a list of 19 priority indicators that offer the greatest return on investment in terms of economic impact.

- Pros: Reduces overwhelming number of indicators to a tangible set deemed most effective, making it easier to advocate for policy change and monitor results.

- Cons: Retains the piecemeal approach, ignoring potential synergies, complementarities and contradictions, while a resilience framework relies on multidimensionality to properly encapsulate a complex concept.

Solution 3: An integrated framework.

Advocated by: Stockholm Resilience Center

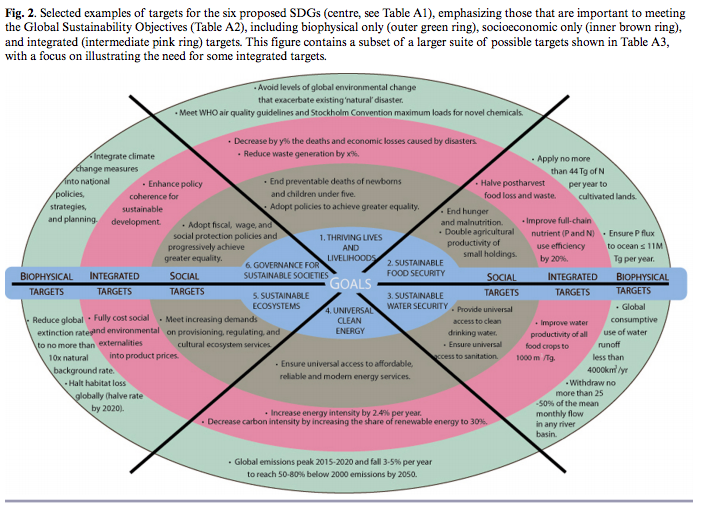

Another Scandinavian think-tank, the SRC has published a paper in Ecology and Society proposing a framework for approaching the SDGs which is both specific and allows for synergies, including socioeconomic, biophysical and integrated indicators along six different dimensions.

- Pros: Incorporates synergies and tradeoffs, focusing on a tangible set of goals which can be understood in context.

- Cons: Potentially too complex to generate widespread public buy-in, difficult to incorporate into the silo mentality of traditional policymaking.

There are no easy solutions to effective implementation, but drawing on the above, as-well as relevant work by the Food Security Information Network, allows us to propose a few rules of thumb for effectively implementing the SDG’s:

- Emphasize flexible programming which acknowledges the complexity of development policymaking, underpinned by a common framework of values.

- Institutional focus and specialization should be encouraged in order to deliver on specific goals, under the oversight of coordinating bodies capable of understanding the dynamic ecological and economic mechanisms at play.

- Tangible indicators matter, which is why food security focuses on concrete outcomes like the MUAC and dietary diversity. These can be objective or subjective, quantitative or qualitative.

- Toolboxes for data modeling and analysis should be easy to use and open source, so anyone can tweak and improve upon them.

- Finally, harness mobile technology to collect data in near real time, allowing for continuous assessment and feedback.

Once the dust of the UN Annual General Meeting has settled, we will likely be saddled with an unwieldy set of vaguely defined indicators born out of political compromise. As researchers, policymakers and technocrats, it is our job to turn these into effective tools for development. Opinions differ, as they should in such an ambitious undertaking. As we move forward, we should keep these tradeoffs in mind knowing that there are no silver bullets, only rules of thumb.