In a previous post, I discussed how daily cooking produces smoke that is killing millions of people every year in developing countries. One possible solution to easing the health, environmental, and economic burdens of cooking with solid biomass fuels is switching to the use of cleaner-burning cookstoves. However, despite their potential benefits, there has been “puzzlingly low” demand for fuel-efficient cookstoves. The low demand for cookstoves has generated much debate within the international development community. Resolving this debate would allow policy-makers to tailor strategies to target what works and not waste resources on strategies that don’t work.

One active question is whether low adoption of cookstoves is due to lack of adequate product information or due to household financial constraints (for example, the Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves divides its “Demand Creation” strategy into two parts: (1) consumer awareness and (2) consumer finance). We examined this question in an experimental setting in rural Uganda and recently published our results in the Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. This work is co-authored with Theresa Beltramo, Garrick Blalock, and David I. Levine, and we extend special thanks to Joseph Arineitew Ndemere, Juliet Kyayesimira, Stephen Harrell, and the Center for Integrated Research and Community Development (CIRCODU) for managing field-based operations.

We ran the experiment in 36 parishes in southwestern Uganda and had more than 2,200 respondents participate. Upon arriving in a new parish, we held a community-wide sales meeting; anyone with an interest could attend the meeting. At the sales meeting we enumerated a basic demographic survey then randomly split participants into four groups. The groups then simultaneously received one of four informational marketing messages about the fuel-efficient cookstoves: (1) “this stove can improve health,” (2) “this stove can save time and money,” (3) both messages combined, and (4) no message. This last control group did not receive a marketing message, but instead held a discussion about regular cooking practices. Then we re-assembled all participants, did a live cooking demonstration with the cookstove for sale (Envirofit G-3300), and explained how the sealed second-price auction worked (i.e., participants submit sealed bids for the cookstove, then the highest bidder pays the second highest price).

Each participant had the chance to participate in two auctions. One was a “pay within a week” auction. The other was a “time payments” auction that allowed the winner to pay in four equal weekly installments. After revealing auction outcomes, the sales team collected the deposit (25% of the sales price) from the winning bidders. The pay within a week auction winners then had seven days to bring the rest of their money and collect the cookstove. The winners of the time payments auction paid the remaining sum of the sales price over the four weeks, but received their stove immediately.

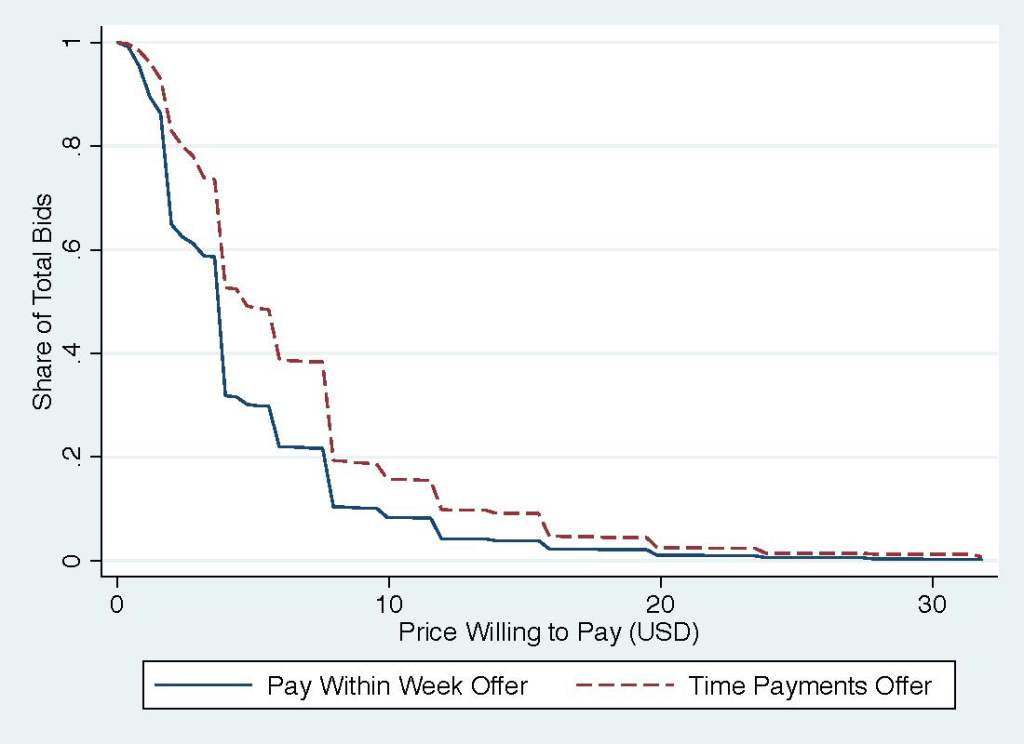

The average bid for the stove was USD$4.86 in the pay within a week auction and USD$6.83 for the time payments auction. This is a 40% increase in willingness to pay for the fuel-efficient cookstove when liquidity constraints are lessened and the difference between the two average bids is statistically significant (p<0.01).

The figure below shows the sample-wide preference for time payments by plotting the share of respondents by bid amount for each auction type. The curve for the time payments auction lies to the right of the pay within a week auction curve, indicating that at any given price a larger share of respondents bid that amount in the time payments auction than in the pay within a week auction. There are no statistically significant differences in average bids across the groups receiving the four marketing messages in either auction type.

An additional interesting finding is that female respondents consistently bid about 20% less than male respondents in both auction types. This finding is consistent with other work on cookstoves, which finds that while women may have a stronger preference for the cleaner-burning stoves, they have less authority over household finances.

These findings contribute evidence to the current debate concerning household barriers to purchasing cleaner-burning cookstoves. Our research shows that relieving household financial constraints is more effective than relieving informational barriers in encouraging the purchase of cookstoves. Additionally, our findings support others that have found gender to be an important determinant of willingness to pay for cookstoves.

The paper’s authors thank the United States Agency for International Development, the Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future at Cornell University, the Institute for the Social Sciences at Cornell University, and the Cornell Population Center for funding the study.

Have you all studied how cooking is traditionally done in the communities where you wish to sell these stoves? Have you got a cultural anthropologist on your team who would think about how these stoves might relate or compare to traditional cooking methods? For example, Can traditional foods be cooked on this stove? Will the food taste the same? Will the same amounts of food be easily prepared? Does the same kind of biomass work in the stoves as it does with traditional cooking?

The way we cook is a deeply embedded part of everyone’s culture. Just because it improves health or saves time and money might not be the point. Tiny example: we can make s’mores in a microwave, but they just aren’t the same–the best ones are made over a campfire.

In other words, changing how an ethnic culture cooks is asking a lot, and I’d expect resistance unless the issue were somehow forced by external causes. On the other hand, I wonder if this idea might catch on among refugee groups who have had to be displaced from their native setting–their culture has already been upset by displacement and they may be at a point of being willing to adopt new cooking methods too.

Hi Linda (full disclosure for any readers, Linda is my mom),

I think your comment is exactly correct. The way things taste and also the ease of use of an appliance in a kitchen matters a lot. To specifically answer about the logistics and make-up of our team. We had a team of Ugandan social scientists from various fields helping us do preliminary investigative work in some test communities before the roll-out of the experiment. In the post, you can click on the link to CIRCODU, which was the Ugandan group that we worked with if you want to see more details on their background and collective experience. We touched on many of the topics you brought up in community focus groups, but perhaps not all of them.

To touch on your bigger question about how much these new stoves are used. This post is based on the first in a series of papers, and it only looks at the binary decision of purchasing a new stove (what economists call the extensive margin) rather than the intensive margin (how much the technology is used once it is owned, the topic you are raising). So the short answer is that, in this paper, we don’t tackle the question you are raising.

The longer answer is that we are currently working on another paper that will delve much more deeply into the topic you raise (use on the intensive margin), but a preview of those findings is that households seem to use the cooking technology that works the best for whatever they are cooking (just like most of us do in our own kitchens). The fuel-efficient stoves are designed to be very heat efficient, and as a result they get very hot, very quickly and thus are superb for boiling tea. However, due to their insulated collars and heat-efficient design, the fuel-efficient stoves are not really that great for lower heat activities such as simmering beans or rice (common dishes in much of the world). And just like none of us would cook a steak (or s’mores) in the microwave, it looks like rural Ugandan households are no different. They seem to use the technology most appropriate to what they currently want to cook.

Our current paper is targeted more to policy makers like the Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves which currently list their two main pillars to demand creation for cleaner burning cookstoves as “consumer awareness” and “consumer finance.” To a group like the GACC, we hope that our research would inform how much resources they should spend on “consumer awareness” and on “consumer finance.” Based on what we found in Uganda we would weight funds allocated to “consumer finance” much more heavily than funds allocated to “consumer awareness.”

Cheers,

Andrew