Confession: I have posted pictures on Facebook during fieldwork for the explicit purpose of showing off how worldly and humanitarian I was. Yes. Like this girl.

Yes, I am white and I am American. And while I have no reason to believe all white American students abroad are as infuriatingly idiotic as I was, I do think the explicit calling out of this behavior in research and academic circles is virtually nonexistent outside of relatively flimsy references made by internal review boards or (maybe) research manuals.

This online behavior is not something that’s limited to Americans, or white people, or westerners, or students. It holds in any circle where contextual and historically defined dynamics of power are at play, even when these dynamics are unnoticed by those involved.

On the margins

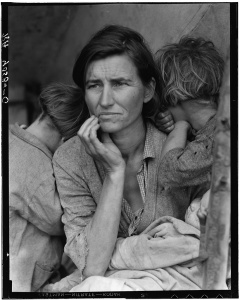

Five years ago I was in China researching infant feeding practices of migrant women. I had just read The Grapes of Wrath, and, interested in how the current situation in China compared to the migrants during the Great Depression, I spent hours googling a photograph called Migrant Mother.

The photo, which now hangs in the Library of Congress, is of a migratory sharecropper and her children. It was taken by Dorothea Lange in 1936 and initially published in the San Francisco News. Lange did not get the woman’s name or have any kind of memorable discussion with her; she just took a few photos and asked her some basic demographic details.

Migrant Mother is a brilliant and powerful photo that is known as the iconic image of the Great Depression. After its publication, it immediately prompted tens of thousands of dollars in food aid to the farm workers in California and increased awareness of their extreme poverty during that time.

But the identity of the woman in the photo was not, at least publicly, known (it’s unclear whether the woman saw her picture in the paper when it first was published) for more than 40 years. A reporter finally identified her as Florence Owens Thompson, living in Modesto, California.

According to reports, Thompson and her family were not happy that they had unknowingly become the poster children for poverty. They voiced concern that the information surrounding the photo wasn’t even accurate. The description given by Lange said that they had sold their tires for food; per the family, they never had any tires to begin with. Thompson gave permission for the photo to be taken but was under the impression that the photos would never be published publicly, and even Lange herself notes that she failed to send the final prints to the family as promised.*

The point is this: Lange asked Thompson if her photo could be taken and Thompson said yes. The problem was not lack of permission. The problem was that Lange had control over that photograph, and there was little communication about what that actually meant. Lange controlled where the photo ended up, as well as how Thompson and her family were portrayed.

The Thompson family was turned into a symbol of poverty. Lange, widely respected for her work in social justice, likely saw the family as such and knew the power that symbol would have on policy-makers and humanitarian aid. But in doing so, by turning the Thompson family into a symbol, she also took away their power. She controlled their identities. They had just one story, and that story was of poverty, whether they (as the story’s central characters) agreed or not.

Reformulating ideas of power and ownership

These themes of power and ownership over what we share online are the linchpins of the age we live in. There is a general agreement that we need to think more carefully about the photos we share online, and ensuring that people retain some control over their own images is part of that. For example, the options of un-tagging or hiding posted photos are common features of most social networking sites now.

But we desperately need to take a more considered, deeper reflection when posting about the people involved in our research projects, whether participating directly or simply as geographically convenient bystanders.

- Power

Researchers and academics usually have a strong code when it comes to the privacy of their research subjects. But the line between what is private (and therefore protected) or public is now blurred thanks to how we share experiences with each other on the Internet.

A few years ago, a friend of mine on a medical mission abroad posted numerous photos of the procedure room she was working in. The photos included patients in the middle of procedures, parents holding children who had just been operated on, and patients who were post-operatively resting. The captions described their problems, where they were from, and why they were selected for the free medical care (mostly because they were from rural areas with no health center).

My friend was rewarded by the overwhelming amounts of ‘likes’ and comments in the photos. She and those who commented on or ‘liked’ her photos didn’t consider that they were reinforcing the social structures of power in an already age-old narrative: she was the savior, the bringer of goodwill to poor benighted people.

And by posting their private, possibly shameful photos, she also clearly did not see the people she was serving as her equals. But more than that, because they were in the vulnerable position of needing free medical care, even if she had asked their permission, explaining that her friends back home wanted to see their babies’ recoveries, would they have felt they had power to say no?

Alison Hayward, in her essay “There is no HIPAA in Haiti?”, formulates the problem as a “gray area” in patient privacy. She explains that, “as yet, no such organized bodies review the clinical care provided by traveling healthcare workers, nor does any review board or hospital committee discipline their staff based on inappropriate use of information or photographs gathered while on international ‘mission’ trips.”

Hayward urges practitioners to critically assess their stereotypes and portrayals of patients abroad. But it is also important to expand this reflexivity beyond the patient-doctor relationship and better define the importance of representation.

- Representation

Who is represented and how has to do primarily with subjectivity. By subjectivity, I mean the ways in which different people perceive, think, fear, and judge. A simple headshot of a woman and her children during the Depression-era turned into an icon because of what it represented. A photo of your field site is susceptible to the same subjectivity.

This is crucial. Subjectivity has to do with both how a photo is presented and how people perceive that photo. It is not enough to think before you post; if you are posting photos of your field site or even something that might look like your field site, you automatically become the representative of that site to your audience. And how your audience perceives that scene depends on their preconceived, subjective notions of something that actually may be the opposite of what you are trying to depict.

Often the perception of poverty, helplessness, and vulnerability of rural low-resource areas in the world has been shaped by humanitarian organizations and the media in order to bring awareness to important issues of injustice or structural inequalities.

But this single narrative, produced and re-produced through our social media coverage, has become less an accurate portrayal and more the enforcement of a stereotype; it is colloquially known as poverty-porn.

- Identity

Which brings me to identity. The distinction between how you identify someone in a photo and how they identify themselves is important.

During my first year as a doctoral student, I was uneasy with how photos were used on powerpoint slides during lectures or seminars. Professors and students would casually present HIV statistics next to photos of their field sites (I assume for visual appeal), which usually included a non-white woman, often with children, whose appearance was consistent with the poverty-porn narrative.

Think about that.

HIV, malnutrition, and poverty are deeply connected with stigma and shame almost everywhere in the world. And these images are used – maybe with the permission of the subject, but I doubt it – to illustrate what a person living under those circumstances looks like.

As if life weren’t hard enough for all of us, now we live in an age where someone who has no interest in being victimized can have their face broadcast to classrooms around the world as the representative of someone with HIV, who can’t take care of her children because she is too poor to feed them. And the next generation can look at this photo, see that face, and bask in the splendor of knowing that they are here learning how to help that person, wholly and forever unaware that the presenter merely seized and appropriated that face to improve the visual appeal of the presentation without a second thought.

Online, out of context, images are so easily turned into symbols. The people disappear; the stereotype of HIV, poverty, and ‘the other’ is all that is left for the audience.

Reexamining our sharing standards

How we share our fieldwork experiences matters. Photos are powerful things, and sometimes permission isn’t possible or necessary, just like in your life at-home with your at-home friends.

But researchers are in positions of power, and that power now is interspersed into our personal lives through social media and the Internet.

We have the responsibility to critically examine how we represent the people in our field sites and how we reinforce the pre-conceived stories our audience may hold about those places and people. We shouldn’t drain the people we work with of their dignity or agency because we are careless with our social media accounts. They have likely spent their lives constructing their identities outside of the poverty/disease/marginalized-person narrative.

Power, representation, and identity must be included in our codes of ethics and privacy. Maybe one day we will have an explicit social media code about posting Facebook or Twitter photos. But until that time, at least consider a re-examination of your own sharing standards, whether you are a student, a researcher, a professor, or a Facebook user.

* If you’re interested, here is a more in-depth account of the Thompson’s story.

Excellent points throughout. As a photographer that often focuses (if you’ll pardon the pun) on the genre of street photography, I am often conflicted by my motives to capture candid, seemingly banal moments of people going about their day, whilst simultaneously doing so through an an anthropological lens, if I might call it that. Anthropology, to me, is a way of attempting to see and understand the world around me — which is to say, an attempt to see and understand myself and others; which is also to say, to attend to power dynamics and the reification of subjevtivities as they are renegotiated through time. Yes, anthropology is a discipline, with all its historical roots within the larger social, political and biological sciences, and that makes it problematic at times. But an anthropological lens helps me see the banality of day-to-day life as actually quite unusual, or at any rate, peculiar to a specific time, place, space and people.

It gets problematic because I’m more interested in essentialising that which I see, in a deliberate manner, and through that essentialisation, to essentialising myself and my perspectives. And that essentialisation is fraught with dangers of representation. ‘How then to proceed,’ is a question I frequently ask myself, given that I am increasingly interested in focusing on the ways the self portrays through the intercession of space, place and time. On the surface, I might suppose this question reveals why much of my recent work has strong undercurrents of political and social unrest, of alienation, discrimination, exoiticisation and isolation. Beyond supposing, I know I would like to see more of my personal work move toward these themes, because I feel there is a real story there: not the story of the person being photographed, per se; and certainly not in the photograph itself; but a story about the photograph’s viewers — a mirror of sorts, reflecting back a viewer’s own experience with political and social unrest; alienation; isolation; and so on. Sure, the story being told is individual, in that we all map out and project our subjectivities onto what we bear witness to, based on our personal histories, or in this case, to the photographs we view. But the story unfolding, then, is also the story of us, both individually and collectively. And that is where things get tricky for me, because photography is really about capturing a slice of time and presenting it as if a whole story is bound within its frames. But a photograph itself is ambiguous and tells us nothing. It is rather an invitation to deduction, nothing more. The real story unfolding is that of the viewers’, whose own personal history is what impresses their reception of the photograph before them.

Susan Sontag and Judith Butler have written extensively about this. And I would like to see more written. I really appreciate your perspective on this, and the points you make will encourage me to carry and utilise my camera with even more caution than before.

Thanks!

Brian