Research on the welfare effects of price changes is relatively abundant, especially since the recent global food price crisis. The general conclusion that emerged from these studies is that many households must have been pushed into poverty as a direct consequence of being exposed to food price shocks. For example, in their now-famous paper, Ivanic and Martin (2008) find that around 100 million households fell into poverty due to the global food price crisis of 2007-08. In Uganda, the country of my research focus, empirical studies have focused on either the extent of price transmission between international and domestic prices or on the impacts of soaring global prices on poverty (Bussolo et al, 2007; Benson et al, 2008; Boysen, 2009; Ulimwengu and Ramadan, 2009; Kaspersen and Foyn, 2010; Simler, 2010). Their results suggest that Ugandan markets are integrated into the global food market although only imperfectly. Consequently, increases in global food prices also affect domestic markets and lead to increased poverty (e.g., Boysen 2009). Other studies suggest that the revenues of both net sellers and net buyers have increased as a consequence of high food prices (e.g., Ulimwengu and Ramadan 2009).

Although these studies provide some usual insights on the impacts of food prices on poverty, household revenues, or welfare, they rely on some assumptions that are difficult to sustain, particularly in developing countries. For example, the implicit assumption in almost all of the previous studies is that households are operating within complete and competitive food and labor markets, requiring separation between consumption and production decisions. However, many studies have shown that there is little evidence in favor of this separability assumption because farmers generally have some preferences towards working on their own farm or off-farm (Huffman, 1980; Lopez, 1986), home-produced goods and market-purchased commodities are not necessarily perfect substitutes (Imai et al, 2011), and/or transaction costs may be sufficiently high that it becomes unprofitable for a farmer to participate in a market, leading to autarkic behavior (Key et al, 2000; Henning and Henningsen, 2007). In the presence of one of these situations, production decisions and consumption preferences cannot be treated as two separate problems, meaning a model that incorporates the non-separablity is needed to properly study the welfare impacts of price shocks.

In an ongoing research paper, Gabriella Berloffa and I focus on labor market imperfections as the primary source of market failures and measure the extent to which these imperfections affect the magnitude of both price elasticities and welfare effects of food price changes. In computing these money-metric welfare measures, we diverge from almost all the previous studies in two different ways. First, instead of applying hypothetical price simulations as is commonly done, we take advantage of the availability of household panel data, collected during periods of stable and high prices, that allows us to take account of changes that households really experienced. Second, and contrary to virtually all previous studies, we derive an expression of compensating variation (CV) encompassing labor market frictions and shadow effects of price changes.

We use a balanced panel data of 2,310 Ugandan households collected in 2005/6, 2009/10, and 2010/11 by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBoS) as part of the Living Standards Measurement Study-Integrated Surveys on Agriculture (LSMS-ISA) effort by the World Bank. We find that household data support the non-separable model, implying that production and consumption decisions should not be modeled as two separable problems. Second, when we compare results between the non-separable model (that accounts for labor market frictions) and the separable model (that assumes perfect and competitive labor markets), the results reveal that the welfare effects of food price changes are lower in the non-separable model and different in signs and magnitudes for sub-groups of households.

In particular, the results show that the welfare effects present opposite signs in the sub-period 2005/6-2009/10. Indeed, while Ugandan households as a whole have benefited from high food price increases between 2005/6 and 2009/10 by around 15% (meaning that they have to decrease their total expenditures in 2009/10 by 15% to reach the utility level achieved in 2005/6), they lost from these price increases by 9.7% if we incorporate virtual or shadow effects due to labor market frictions. This result suggests that degree of imperfections in the labor market was so important such that they overturned the welfare gain obtained under separable models.

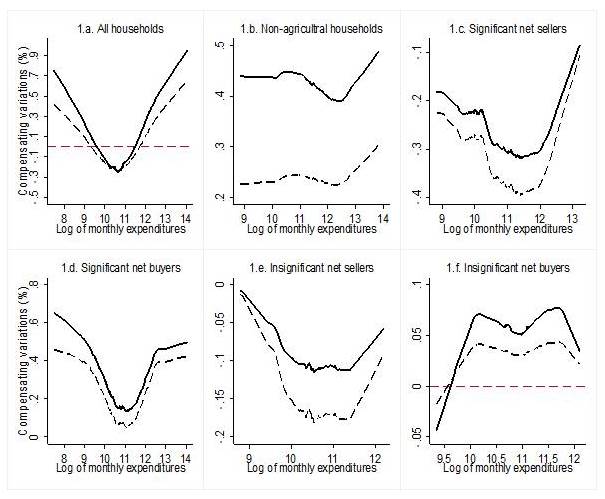

Between 2009/10 and 2010/11, characterized by marginal increases in real consumer prices (21.4%), the average Ugandan household lost from price increases by around 4.2% in the separable model and 1.9% in the non-separable model. In terms of net market positions, although net sellers gained from high prices and net buyers lost, the magnitude of these gains and losses is substantially different under separable and non-separable models, but also between different sub-periods. Particularly, welfare estimates of price changes are found to be globally over-estimated under the separability hypothesis, while the non-separable model implied smaller gains for net sellers and smaller losses for non-agricultural households and net buyers.

This result is standard in the agricultural household model literature where agricultural households are generally found to react relatively less to price changes than when we assume a perfect household model. Hence, although we find that net sellers did benefit from high food prices, and that non-agricultural households and net buyers did lose from these price increases, the magnitude of these impacts will certainly be over-estimated under the assumption of perfect labor markets, and in some circumstances, we can wrongly conclude that households gained from high prices while in reality they have lost, or the other way around.

Finally, we find that even within the same sub-group of households, welfare estimates are substantially different along the distribution of household expenditures, with households located around the middle of the distribution reporting the largest welfare gains or the lowest welfare losses.