Uninsured risk exposure and the experience of uninsured shocks in low-income rural communities cause serious welfare losses and distort behaviors, potentially even resulting in poverty traps (Rosenzweig and Binswanger, 1993; Morduch, 1994; Carter and Barrett, 2006). However, conventional insurance products are routinely unavailable due to moral hazard and adverse selection problems, as well as high transaction costs in infrastructure-poor areas. Index insurance products are cheaper and more suitable alternatives in these environments, as discussed in an earlier post on this blog by Nathan Jensen. As a result, there has been a significant push to expand index insurance offerings in the developing world over the past decade. But, there is little empirical evidence demonstrating that index insurance generates welfare gains households that purchase policies. Indeed, the low uptake of index insurance products introduced across a range of countries hints that many prospective buyers believe index insurance does not deliver welfare gains (Giné, et al., 2008; Binswanger-Mkhize, 2012; Cole et al., 2013).

The arid and semi-arid lands of East Africa present an ideal setting for impact evaluation of index insurance. Pastoralists in these regions rely on livestock as their main source of sustenance (see Russell Toth’s post on this blog), which presents an opportunity to better observe behavior over a narrow class of assets. A pilot index-based livestock insurance (IBLI) product that was first introduced in northern Kenya in 2010 and expanded into southern Ethiopia in 2012 has allowed careful analysis of the impacts of index insurance, which includes recent works by Jensen and coauthors and Janzen and Carter (2013), lending support to the growing push to expand IBLI access. As a further endorsement of the positive impacts of IBLI, the Government of Kenya is exploring with the World Bank a nationwide program to provide IBLI coverage to 100,000 households for 3-5 years.

Deeper insights into the welfare impact of index insurance can be gained by looking beyond traditional wellbeing measures such as income, wealth, consumption, investments and schooling. In this regard, measures of subjective wellbeing (SWB) are excellent candidates. For example, studies on the famous Oregon Medicaid experiments find mixed results on the effects of the program on physical health but significant positive impacts on self-reported physical and mental health (Finkelstein et al., 2012). Similarly, studies of the US Moving to Opportunity (MTO) randomized housing mobility experiment find significant effect on subjective wellbeing but little impact on economic or educational outcomes (Ludwig et al., 2013). In instances such as these, impact assessments that look solely at conventional measures of welfare may underestimate the true value of programs.

In an ongoing research project, Chris Barrett, Erin Lentz, Birhanu Taddesse and I use three rounds of data collected between 2012 and 2014 in Borana zone of southern Ethiopia to identify the impacts of IBLI on respondent’s SWB. These SWB measures are designed to allow for interpersonal and intertemporal comparisons. IBLI uptake is likely endogenous in the sense that peoples’ subjective life satisfaction is likely correlated with their subjective assessment of risks, their planning horizon, and other unobserved factors that influence insurance uptake. We exploit the randomized experimental design of IBLI roll-out to address the potential endogeneity of IBLI uptake.

An additional complication of estimating the SWB effects of IBLI uptake is that the ex ante and ex post wellbeing effects may differ. Insurance that is ex ante welfare enhancing for risk averse households may be ex post welfare reducing once the risk has passed, especially if the coverage ends without payout but having cost the household a premium payment. In this case, with the benefit of hindsight, the insured households would have been better off financially had they not bought the coverage. The possibility of such “buyer’s remorse” can confound valuation of insurance coverage.

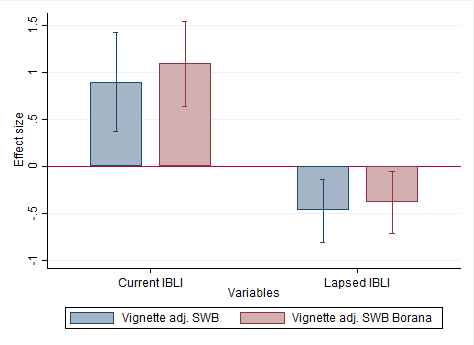

We identify the causal effect of IBLI uptake on SWB by exploiting randomized incentives to induce IBLI purchase and intertemporal variation in IBLI uptake, using coverage active during the survey to capture ex ante welfare effects and coverage that had lapsed by the time of the survey to capture ex post impacts. IBLI did not pay out during our study period, therefore any ex post effects would reflect exclusively buyer’s remorse since purchasers were left unambiguously worse off financially from having paid a premium for a policy that returned no indemnity payment.

We find that IBLI generates statistically significant SWB gains that significantly exceed the statistically significant adverse buyer’s remorse effects of a lapsed policy that did not pay out. Our results are robust to alternative SWB measures, model specifications, as well as variation in the relevant panel sub-sample analyzed. The clear implication is that IBLI improves buyers’ SWB even over a period when insurance buyers lose money on the policy.

These results are intuitive. Few (if any) of us feel worse off at the end of an insurance coverage period when we lost money because we paid a premium on our health, home, or automobile insurance policy but did not suffer hospitalization, a house fire, or a car accident. The peace of mind effect dominates any buyer’s remorse we might reasonably anticipate. Pastoralists in southern Ethiopia appear to feel the same way. The key insight is that even an insurance policy that does not pay out still improves peoples’ perceptions of their wellbeing, an effect that more conventional welfare measures based on expenditure- or income-related indicators likely would not uncover.