In an earlier post I described how in-kind transfers of staple food grains could be self-targeting in the sense of generating more participation from the poor. The self-targeting happens, however, only if villages offering the transfer choose to provide low cost food that appeals to poor households and not high cost foods that the wealthy prefer. Letting villages choose which food to buy may make the program efficient but could come at the cost of leaving out the poor if villages choose goods that wealthy households want. Which outcome will result from a community process of choosing the food is an open question. While working for the Social Observatory of the World Bank over the last couple years, I had an opportunity to answer this question.

For several years, the Bihar Rural Livelihoods Project (BRLP), a project supported by the Government of the Indian State of Bihar and the World Bank, has been piloting a program that offers a subsidized loan for the purchase of food grains to women who participate in microfinance programs. Crucially, rice, the primary food grain in Bihar, varies enormously in terms of cost, taste, color, etc., so BRLP let each village choose which kind of rice to offer through the loan program. In observing villages’ rice selection, we were able to address the following questions: Do villages choose to buy the most expensive or least expensive rice available? Does the choice of rice determine who participates? Taking these two questions together, is such a program self-targeting or does it lead to elite capture?

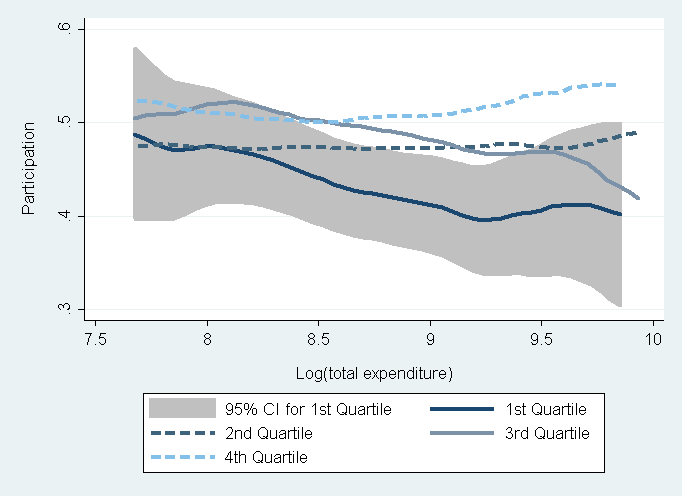

It turned out that in Bihar, villages chose rice along the whole range of the quality distribution. This suggests that letting villages choose which kind of rice to buy will not always lead to outcomes that the poorest most prefer, but it does let us see whether participation according to wealth varies along with the village choice in the way that the theory predicts. The graph below shows the participation rate based on choices that villages make.

The darkest solid line shows the participation rate when villages chose rice that was among the cheapest 25 percent of all the varieties of rice purchased by the program. The lightest dashed line shows the participation rate in the 25 percent of villages that chose the most expensive rice. Comparison of these two lines shows that choosing low cost rice is a way of excluding the wealthiest members. In these villages, participation was highest among the poorest households and declining in household expenditure. In the villages that chose the expensive rice, participation was pretty flat, suggesting that choosing high cost rice does not necessarily leave out the poor. Regression results suggest that wealth is positively correlated with participation only at the very highest prices, which may happen because the subsidy makes even the most expensive rice appealing to poor households, which may be willing, when offered a subsidy, to pay a little more to buy better quality rice.

These results suggest that the combined mechanisms of 1) offering a subsidy on staple foods and 2) letting beneficiaries choose which staple good will be subsidized can be effective in self-targeting in the sense of getting the wealthy households to drop out, but that this outcome is not guaranteed by these mechanisms alone.

See my paper for additional insights from this context, including evidence that this subsidy can actually decrease the amount of food grain eaten (because households in villages that offer subsidies on expensive rice choose to upgrade the quality of their rice) and evidence on the characteristics of villages that are associated with the most pro-poor outcomes.