Environmental shocks are drivers of poverty as well as a fact of life in many rural areas of the developing world. In the developed world, agricultural insurance provides protection from such calamities. But conventional insurance products have not reached many rural households in developing countries due to the high costs of gathering information relative to the size of policies demanded and well-known moral hazard and adverse selection issues that complicate product design and pricing.

Recently, there has been much excitement around the use of index-based insurance as an alternative to conventional insurance products that may extend the rural poor’s access to formal insurance coverage in developing countries (Alderman & Haque 2007; Barnett, Barrett & Skees 2008; Mahul & Stutley 2010). Index insurance provides indemnity payments based on a signal that is related to covariate losses rather than actual and observed individual losses. When signals are chosen properly—easy to observe, exogenous, highly correlated with the insured risk—suppliers of index insurance face much fewer costs associated with adverse section, moral hazard monitoring, and validation of claims than they would if they were offering conventional policies.

Growing enthusiasm for index insurance among economists and development organizations has led to a proliferation of pilot projects across the globe.

Basis risk, or the risk that insured households continue to face after purchasing an index insurance contract, is a widely recognized “Achilles heel” of these new products and is thought to be quite sizable by some (e.g., Miranda & Farrin 2012). Until now, however, very little energy has been spent on examining the quality of the index insurance products for smallholder agriculturalist households in developing countries. No pilot project to date appears to have examined how insured individuals’ actual losses correlate with the index on which the index insurance contract is based. If that correlation is weak, index insurance offers little risk coverage; indeed if the correlation is negative, it may increase the risk that some insurees face. For those households, index insurance represents a gamble in spite of the ‘“insurance” label: households pay a fee for the chance of a payout that increases the variance of their stochastic income. Commercially loaded index insurance, for which the premium exceeds the actuarially fair price in order to cover the insurer’s costs, can therefore be more like a lottery ticket than an indemnity insurance policy for some households. Without close analysis we do not know where index products fall on the spectrum between full risk coverage and lottery tickets, and for which clientele.

In response to this need, my new working paper with Chris Barrett and Andrew Mude studies the distribution of basis risk associated with the Index Based Livestock Insurance (IBLI) product in Marsabit, Kenya.

IBLI was launched in northern Kenya in January 2010 to insure pastoralists against livestock mortality associated with drought. The insurance policy payouts are determined by an index of predicted division-average livestock mortality. The IBLI index was developed using statistical methods to relate historic livestock mortality to remotely sensed Normalized Differenced Vegetation Index (NDVI) measures and minimize basis risk.

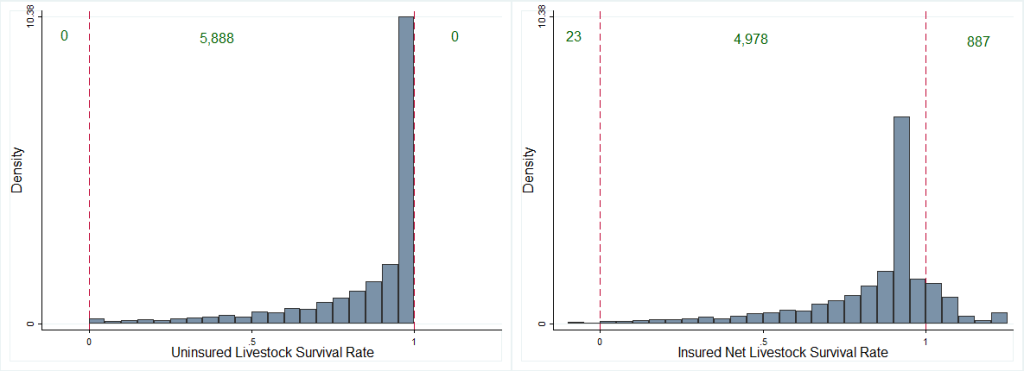

We use four rounds of data from an annual household survey (2009-2012) and IBLI index values to study the distribution of basis risk associated with IBLI across eight insurance seasons. Histograms of the reported livestock survival rates and simulated net survival rates—the survival rate less the loaded and unsubsidized premium plus indemnity payments—illustrate the impact of IBLI coverage and allow us to glean insight into the magnitude of basis risk.

IBLI coverage clearly changes the domain, expected value, and shape of the distribution of outcomes. The average net impact of full insurance on the eight season within-household distribution of outcomes is to improve skewness at the cost of reducing expected outcomes (due to the premium) and increasing variance (due to excessive indemnity payments). But those statistics alone cannot tell us if IBLI is providing insurance coverage or access to a lottery for the majority of households.

To address this question, we model expected utility with and without IBLI coverage. Because IBLI premiums include commercial loading, they reduce expected outcomes and risk averse households will only prefer IBLI coverage if it provides insurance coverage rather than a gamble. We find that most—but not all—risk averse households enjoy net benefits from purchasing IBLI, even at unsubsidized rates.

Our analysis supports the commonly held but rarely examined belief that index insurance suffers from considerable basis risk. But, we also find that IBLI nonetheless offers significant benefits to most households, even at commercially loaded premium levels, because it provides indemnity payments during critical periods of high livestock mortality. For that majority, IBLI operates as advertised, offering an insurance product against large drought shocks. But any index insurance product necessarily offers incomplete coverage. The community promoting these innovations might take greater care to ensure that we are indeed filling missing markets for insurance, not for lottery tickets.

Its quite informing.