Although the engineering and ecological origins of the term resilience are well known (see Holling for a nice review), the concept of resilience as employed by the international development community might go beyond the theories of returning to equilibrium (i.e., “bouncing back”) and stability domains. For donors and humanitarian/development organizations, resilience promises to bridge the traditional silos of humanitarian relief and development programming. Take, for example, the USAID’s definition of resilience, which appears in the agency’s Policy and Program Guidance on resilience:

For USAID, resilience is the ability of people, households, communities, countries, and systems to mitigate, adapt to, and recover from shocks and stresses in a manner that reduces chronic vulnerability and facilitates inclusive growth. (p. 5)

But can resilience live up to that promise, or is it simply a repackaging of conventional interventions?

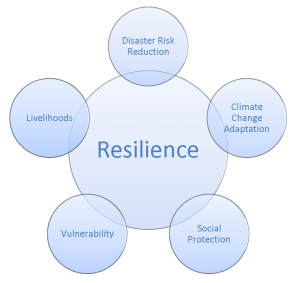

While the outpouring of resources available for resilience building indicates that the donor community has largely bought into the concept of resilience (and snazzy acronyms) – see, for example, the EU’s factsheet on AGIR and SHARE, DFID’s BRACED project, or USAID’s announcement earlier this year about RISE – the current lack of consensus over resilience measurement and impact assessment means that some NGOs are certainly plugging the term “resilience” into proposals replete with typical development activities. Nonetheless, resilience has developed as a sort of unifying framework, an umbrella under which best-practices can be drawn from disaster risk reduction, climate change adaptation, social protection, vulnerability, and livelihoods approaches. Donors are demanding integration and appropriate sequencing of humanitarian and development interventions focused on resilience, and NGOs are anxious to implement projects that address the root problems of chronic poverty and cyclical emergency response.

Some development scholars, such as Christophe Béné and his coauthors, argue that resilience is not inherently pro-poor, and that there is a potential trade-off between resilience and well-being. The significance of this well-grounded fear depends greatly on how we choose to measure resilience, and suggests a need for resilience measurement tools that focus not only on well-being, but disproportionately on the well-being of the poorest and most vulnerable members of society.

While the threat of policy whitewashing is largely (and perhaps not surprisingly) absent from the economics and practitioner discourses, the topic has stirred up quite a controversy among sociologists and political scientists. For example, Brad Evans and Julian Reid argue, in the summary to their book, that the widespread use of the word resilience is “disempowering endangered populations of autonomous agency,” while Jonathan Joseph argues in this JCMS paper that resilience “shifts responsibility away from the international community and onto local actors who are now held accountable for failures of governance.” On the other hand, in his recent book on the subject, David Chandler takes a more nuanced view when discussing the UK’s National Adaptation Programme:

Governance is therefore no longer seen to be based upon ‘supply-side’ policy-making but rather on the understanding of the processes and capacities that already exist and how these can be enhanced. In this way, resilience-thinking should not be understood narrowly, as merely building the capacities of individuals and societies, but more broadly, as a rationality of governing which removes the modernist understanding of government as a directing or controlling actor, capable of understanding, planning and implementing as if it had perfect knowledge in a fixed and stable world amenable to Newtonian cause-and-effect understandings. (p. 212)

For the economist or practitioner, a crucial takeaway from the sociology and political science debate is the importance of including power relations and indicators of social vulnerability in our theoretical and empirical resilience models.

Ultimately the proof of the pudding is in the eating; the fate of the term lies in the adoption, or lack thereof, of tools for measuring resilience and assessing the impacts of resilience building interventions on resilience. Without a dedication by the international community to measurement (and a willingness on their part to be held accountable for outcomes), resilience may indeed find itself in the buzzword graveyard. This would be a travesty – and not only because I am dedicating my dissertation to the idea – because a focus on resilience has the potential to increase our understanding of poverty dynamics, particularly with regards to shocks; encourage improved monitoring and accountability in programming; bring together disciplines, programming silos, and funding streams; and ultimately target programs and policies efficiently and effectively while alleviating chronic poverty and shock-based poverty traps.

The next post in the resilience series will explore a new theoretical approach to resilience measurement and the implications of the theory for development and humanitarian programming.

On its face the term “resilience” as here used seeks a return to the last place we’d care to go, the status quo.

I agree that this is a risk, although the concept has the potential to push us toward investments that positively impact well-being both sustainably and in the face of shocks. Only when the community reaches consensus on measurement, however, will this potential be realized. The second post in this series will go into detail on one such measurement approach. Stay tuned!

I have two thoughts after having read your post. Note that I’m neither familiar with your specific topic nor with the literature around it.

(1) Resilience, based on your description, seems to suffer from inconsistent definition among users of the term. It reminds me of the term “sustainable” which has many definitions as users. Providing some metrics of resilience would potentially narrow the range of definition of resilience PROVIDED that other users of the term accept the metrics. Rejection of the metrics because they are insufficiently encompassing of the range of definitions of resilience is a possible outcome that (a) you need to consider and (b) may result in wholesale rejection of the metrics. If your intention is to craft a set of metrics that address the range of definitions of resilience you need to consider the risk of dilution of their effectiveness because of the breadth of definition. If your intention is to accept and develop metrics for a more narrowly defined resilience, you may want to focus on a subset of resilience such as “bounce-back” resilience (return to previous status quo) as opposed to “progressive” resilience (surpass previous status quo).

(2) My second thought is really a question. Is your intention to develop a smorgasbord of metrics from which an agency, group, or individual might choose to measure change in which they are particularly interested or is your intention to develop one set of metrics that a the “meta” level define resilience and in the application provide a measure of relative resilience against a scale you establish with the metrics?

Topic sounds really interesting and with many, many potential applications.

The massive, near-frenetic embrace of “resilience” (and I’m speaking here of in the social services, not international development, though clearly the enthusiasm for the subject overflows in this arena, as well)is curious to me, but not unexpected. The goal of the resilience-lovers seems to boil down to, “We will make you stronger so that these assaults–most of which are caused by structural factors–can keep coming.”

So individuals (and their families) are given these tools, and then, when they crumble under these assaults (e.g., systemic poverty, racism and other forms of discrimination and harm, poor access to nutrition, horrendous education, and related inequities)–they are then, to blame. Were the tools faulty? Perhaps not. Were the forces they sought to counter overwhelming? Likely so.