Esteban J. Quiñones is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and is a Trainee at the Center for Demography and Ecology.

Anticipation is a Virtue

A growing literature highlights how climate events, such as extreme heat, hurricanes, and floods, shape migration (Gray and Mueller, 2012; Cattaneo and Peri, 2015; Jessoe, Manning, and Taylor, 2018). Nearly all of these studies restrict their attention to reactionary (ex post) responses to climate shocks, despite the widely held but rarely tested hypothesis that individuals and households also migrate in anticipation of future risks. The lack of research on anticipatory (ex ante) migration is likely due to the difficulty in distinguishing between ex ante and ex post phenomena. To my knowledge, Dillon, Mueller, and Salau (2013) is the only exception.

In my job market paper, I explore whether individuals from rural, agricultural communities in Mexico migrate or reallocate local labor in anticipation of climate-induced crop losses. I develop an approach to credibly disentangle ex ante from ex post responses to temperature-induced catastrophic crop losses in order to assess how information spillovers associated with climate events in rural, agricultural communities influence migration and local labor decisions.

I find evidence of ex ante domestic migration in the early 2000s, particularly among females and households with more labor, in response to the climate-induced catastrophic crop losses experienced by their neighbors. In contrast, I find evidence of increased agricultural self-employment, especially among males and households with more land.

Why Is this Important?

- Over the next few decades, climate change is expected to increase the frequency, intensity, and duration of climate events (Lesk, Rowhani, and Ramankutty, 2016).

- Adaptation gaps: Observed levels of climate adaptation remain low, suggesting that rural households are constrained or adaptation decisions are sub-optimal (Carleton and Hsiang, 2016).

- Poor households in marginalized communities, especially those that rely on smallholder agricultural production for their livelihoods, may be particularly vulnerable to climate change.

- Poor households with limited asset endowments are most likely to respond to climate change through labor reallocation.

Climate Change and Mexico

The adverse consequences of 1°C of global warming in the form of extreme weather events and rising sea levels are already evident. Continued warming beyond 1.5 is likely to result in long-lasting or even irreversible changes, including the complete loss of some ecosystems (IPCC, 2018). In addition, evidence has shown that extreme temperature events are more damaging to crop outcomes than rainfall (Schlenker, Hanemann, and Fisher, 2005).

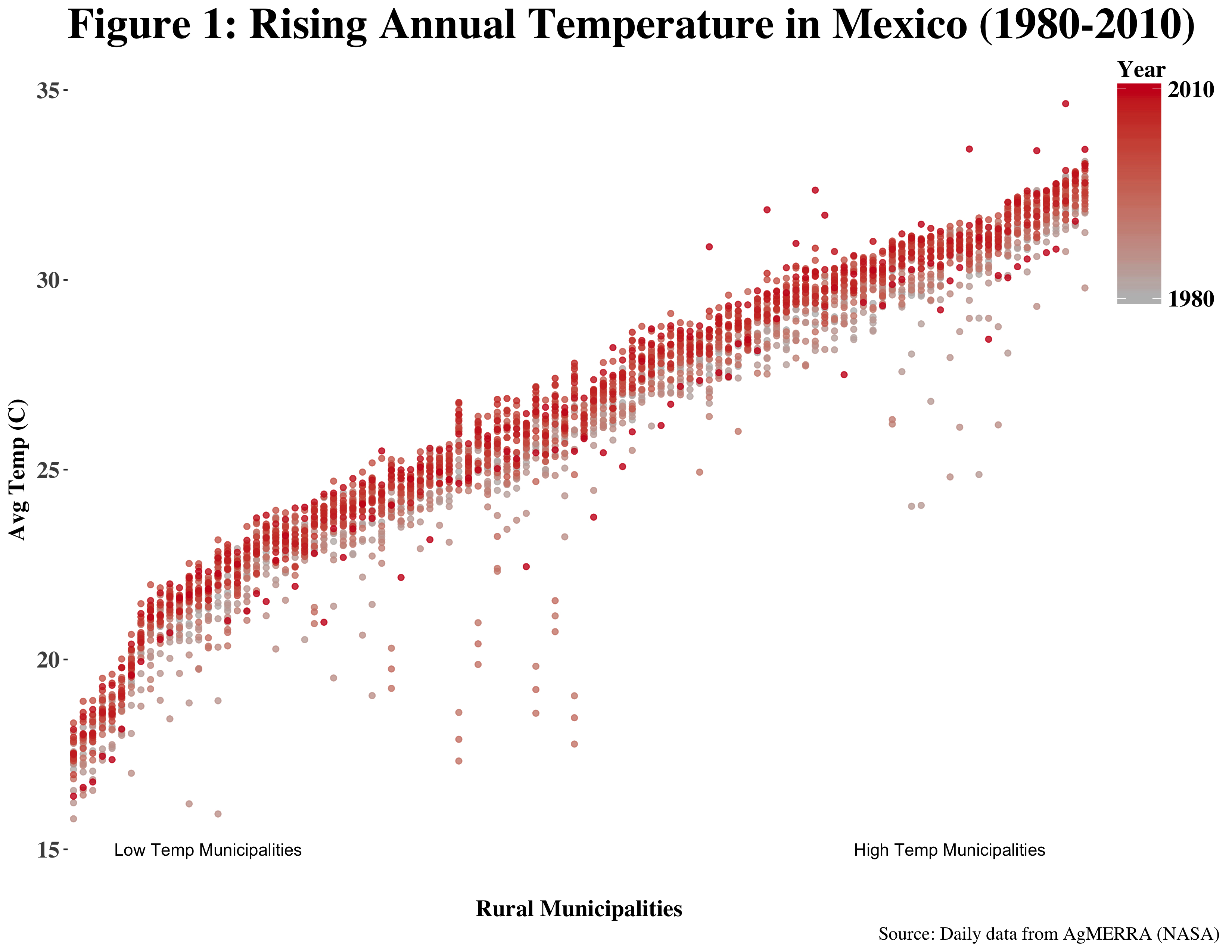

Figure 1 demonstrates that temperature increases were widespread in rural Mexico from 1980-2010. Each rural municipality in the Mexican Family Life Survey (MxFLS) is depicted in a column (vertically). Municipalities with the lowest average temperature are on the left and those with the highest average temperature are on the right. Annual average temperatures are presented in progressively darker hues from light gray in 1980 to dark red in 2010. The lighter under layer and darker red top layer in the plot provide visual confirmation of rising temperatures that are indicative of an increased probability of heat-induced crop shocks.

How Do I Study Ex Ante Migration?

How Do I Study Ex Ante Migration?

I study heat-induced catastrophic crop losses from 2000-2002 in rural, agricultural communities in Mexico and the associated migration and local labor allocations from 2002-2005 among households that did not directly experience crop shocks. Ex ante responses are defined as those in anticipation of a future heat-induced crop loss.

Individuals face uncertainty about the expected income effects of intensifying climate risks. They can learn about the adverse effects of extreme climate events through agricultural outcomes on their own plots and from other households in their communities.

I integrate panel socioeconomic data from the MxFLS with georeferenced, high resolution weather data from the Agricultural Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications Climate Forcing Dataset for Agricultural Modeling (AgMERRA). To disentangle ex ante and ex post responses I study the labor allocations of households who have not experienced catastrophic crop losses in recent years, thereby eliminating the ex post motives. I focus my attention on how individuals in these households respond to the heat-induced crop shocks they observe among their neighbors (within the community). Because this type of learning and response should only be salient for agricultural households in sufficiently agricultural communities, I restrict my analysis to households who own or use land located in communities where at least 40 percent of households own or use land (this second condition is later relaxed).

I instrument for the incidence of community-level crop losses—the proportion of households that experience crop losses from 2000-2002—using a measure of consecutive extreme heat days in each year over the same period. Extreme heat days are benchmarked as deviations relative to long-run conditions. Instrumenting for community-level crop losses with exogenous daily temperature pins down the agricultural mechanism between climate events and labor allocations while minimizing non-random selection of community-level vulnerability to shocks. I then assess if individuals migrate or reallocate labor locally from 2002-2005 in response to the heat-induced crop shocks that they observe among other households in their communities from 2000-2002.

This empirical strategy rests on a number of arguments, three of which I highlight here: (i) heat deviations are distributed as if they are random across municipalities (independence assumption) – this form of exogeneity is plausible conditional on municipality and state controls; (ii) catastrophic crop loss is the mechanism through which extreme temperature deviations influence migration decisions (exclusion restriction) – evidence ruling out alternative mechanisms provides credence; and (iii) remaining selection with respect to household, community and municipality level resilience/vulnerability to heat-induced crop losses likely attenuate estimates (as opposed to amplifying them) – the analytical sample of households who did not experience catastrophic crop losses are less likely to adjust migration and local labor allocations.

Do Individuals Migrate in Anticipation of Harmful Climate Shocks?

I find evidence that household do adapt in an anticipatory manner via domestic migration, though responses differ systemically according to the relative abundance of labor to land. In the 2002-2003 period directly after the heat-induced crop losses of other households are observed, I estimate an average increase in domestic migration of 2.6 percentage points from 2002-2003 (see the blue coefficient in left panel of Figure 2). This is a proportionally large response, representing an increase of 52 percent and is driven by responses from females and households with more labor. These findings, which appear to be strongest among women, are indicative of an ex ante adaptation strategy to climate change aimed at mitigating the risk of a future crop shock.

Males and households with more land relative to labor respond by increasing agricultural self-employment (coupled with a decrease in agricultural wage work). I estimate an average increase in agricultural self-employment of 8.5 percentage points in 2002 (see the blue coefficient in the right panel of Figure 3). These results also constitute a proportionally large response, representing a 53 percent increase in agricultural self-employment. However, these results are, more likely than not, explained by changes in the local demand for and value of agricultural labor as well as access to land.

These results are indicative of a learning from others mechanism with respect to climate risk. Findings are robust to alternative explanations, such as general equilibrium labor shifts, moderate levels of crop loss within the household, drops in productivity, or increased violence and crime. I rely on a mechanism testing method developed by Acharya, Blackwell and Sen (2016) rule out any such alternative explanation. Robustness is also confirmed with respect to confounding shocks, attrition, ex post responses, and the strength of the learning from others signal.

Contributions & Policy Implications

This study makes three contributions:

- Individuals mitigate against the increased probability of destabilizing climate events in an anticipatory manner through domestic migration.

- Adaptation to climate change can take place via a learning from others.

- The appearance of adaptation gaps to climate change may be explained by a nearly exclusive focus on the ex post.

These contributions have three main policy implications:

- Projections of future migration, which do not account for ex ante mobility, may be understated, limiting policy makers and urban areas from preparing for the future.

- Uneven responses to climate change shaped by preexisting labor and land endowments imply that climate shocks may intensify vulnerability to future shocks for some households and potentially increase inequality.

- The effective and efficient design and targeting of climate change mitigation policies should also serve households that reallocate labor in ways that put them and their community at greater risk.