El Nino is upon us with is its inevitable litany of catastrophes. Ethiopia is particularly hard hit, experiencing its worst drought in 50 years. In response, USAID has activated its emergency DART response team, and is channeling $500 million for emergency humanitarian aid.

But this isn’t Ethiopia’s first drought, nor in all likelihood its last. Eight years ago, a coalition of development partners working with the Ethiopian government set up the Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP). Structured as a public works program, the PSNP employs targeted vulnerable households in public-infrastructure projects and pays them in cash or kind, allowing them to eat during the lean months. PSNP payouts are currently received by 8 million people.

The PSNP has become Ethiopia’s first line of defense against drought, at a projected total cost of $2.6 billion dollars from 2014-2020. Understanding its effectiveness in mitigating the long term impact of recurring drought is therefore key. Does the PSNP work?

The Ethiopian PSNP was designed with droughts in mind, based on the premise that pre-emptive transfers directed at the most vulnerable might preempt, or at least mitigate, the need for annual emergency humanitarian aid. It intends to address the funding gap, and the conceptual “blind spot” outlined by Dan Maxwell, between development and humanitarian aid.

An ongoing concern regarding PSNP evaluations is the lack of evidence that it has alleviated poverty. Using a dose-response model, Hoddinott et al (2012) investigate the relative impact of PSNP transfers alone and combined with an asset building program on key outcome variables: yields, fertilizer use, and agricultural investment. They find little evidence that the PSNP alone boosted these outcomes.

However, as its implementers and many of its beneficiaries argue, many of the benefits of the PSNP are perceived in terms of catastrophes averted. The issue is particularly salient since shocks can undo decades of asset accumulation and push households into chronic poverty.

We focus on resilience, a term borrowed from ecology that emphasizes the ability to return to equilibrium after experiencing a shock. To quote a recent IFPRI report, “Resilience focuses attention on the idea that short-term shocks are malign not just because of their immediate effects but also because of their adverse long-term consequences.”

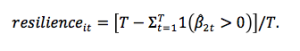

In order to turn the concept of resilience into a measurable indicator, we focus specifically on the ‘recovery trajectory’. Similar to Vollenweider (2015), we distinguish between vulnerability and resilience in that vulnerability is the extent a household’s welfare drops after a shock and resilience is the amount of time before a household returns to its pre-shock level of welfare; the longer it takes for a household to recover, the lower its resilience.

Formally, we define resilience as  Where T is the period under study.

Where T is the period under study.

In doing this, we differ from the moments based approach in that we emphasize ex-post resilience to specific shocks rather than ex-ante resilience. Our approach lends itself to evaluating programs designed to counter certain shocks, like drought.

Here we posit an intervention that decreases vulnerability and increases resilience, though we can also imagine a program that only does one or the other.

A concern with such large-scale impact evaluation is that, because these programs cannot be randomized at a national level for political reasons, our treatment is potentially endogenous. Assuming that the more vulnerable and least resilient individuals are more likely to receive treatment, the program’s effect will be understated under a naïve OLS regression.

Accordingly we use program characteristics as instrumental variables. Notably, we use a) The Woreda (district level) budget and b) whether the payments were in cash or in kind. Both are relevant instruments since they potentially affect the availability of payments; however, since they arise from programmatic rather than household level decisions, they both satisfy the exclusion restriction.

Our results suggest that the PSNP reduces vulnerability by 60% and doubles the level of resilience, significantly improving the post-treatment recovery trajectory.

When a household experiencing drought receives the mean level of PSNP payments (498 birr, approximately $23), their welfare drops less following a shock and recovers more rapidly.

Using our coefficient estimates we can plot the recovery trajectory for beneficiaries receiving the average transfer, and compare it to that of non-beneficiaries (Figure 2).

We use panel data, which allows us to explicitly identify household recovery dynamics rather than rely on strong homogeneity assumptions. This allows us to estimate an instrumented diff-in-diff model with lags to plot beneficiary and non-beneficiary households’ recovery trajectories. We plot the level of transfers, the shocks and the interaction of the two as covariates. We interpret the coefficient on the interaction term as the PSNP transfers’ mitigating effect on households affected by drought.

With temporal lags over past rounds we can trace a recovery trajectory for a given household similar to the one shown in Figure 1. This allows us to empirically distinguish between a households’ vulnerability to shock and its resilience, and in particular allows us to differentiate the program’s impact on each.

The PSNP works. But with its resources stretched thin, the center may not hold. There is an urgent need to channel additional financing through this tried-and-true mechanism, so that households facing El Nino can eat today and recover tomorrow.

Is a full (PDF) version of this paper available?